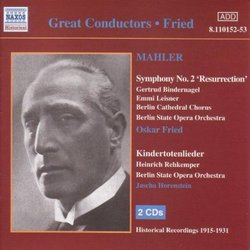

| All Artists: Heinrich Rehkemper, Heinrich Schlusnus, Gustav Mahler, Herman Weigert, Jascha Horenstein, Oskar Fried, Selmar Meyrowitz, Sarah Jane Charles-Cahier, Berlin State Opera Orchestra, Grete Stuckgold, Lula Mysz-Gmeiner Title: Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 "Resurrection"; Kindertotenlieder Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Original Release Date: 1/1/2015 Re-Release Date: 7/17/2001 Genres: Pop, Classical Styles: Vocal Pop, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 636943115220 |

Search - Heinrich Rehkemper, Heinrich Schlusnus, Gustav Mahler :: Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 "Resurrection"; Kindertotenlieder

| Heinrich Rehkemper, Heinrich Schlusnus, Gustav Mahler Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 "Resurrection"; Kindertotenlieder Genres: Pop, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsNaxos' Resurrection of Fried's Mahler's "Resurrection" Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 12/13/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "Oskar Fried's 1924 acoustic recording of Gustav Mahler's Second Symphony (1892), with the Berlin Cathedral Chorus and the Berlin State Opera Orchestra (and soloists) represents a very nearly mad endeavor. Audaciously undertaken by Deutsche Gramophon, it also represents a stunning success and constitutes a milestone, not only in recorded Mahler, but in recorded music. The requirements of Mahler's "Resurrection" Symphony, colossal enough on their own, certainly challenged the limitations, perfectly understood by the engineers, of acoustic mastering. Fried (1871-1941) pared down the performing forces, reconstituting the ensemble as necessary to account for the kaleidoscopic changes of instrumentation. The players addressed themselves, in a small studio, to a large horn; the horn directly agitated a stylus that chiseled groves in a spinning platter. No electrical amplification or equalization took place. It was as crude as it sounds. In Ward Marston's digital transfers for the new Naxos issue, we can nevertheless hear Fried's remarkable interpretation of Mahler's towering symphonic edifice. Fried knew Mahler and received advice from him on early performances of the First and Second Symphonies. This 1924 traversal thus brings us as close to Mahler himself as we are ever likely to get, and it tells us something significant about what has happened to the idea of Mahler over the last eighty years. In 1924, Mahler still appeared as a radically contemporary composer, a modernist in the context of the time. The word "expressionistic" might describe Fried's performance as a whole. He takes the First Movement (Allegro Maestoso) at a fair clip and without sentimentality in the levitating second subject. The cellos and basses bite deeply into the familiar opening figure. The Second Movement (Andante Moderato) benefits from a slightly faster tempo than we expect and gains a hint of irony under Fried's direction. The Third Movement Scherzo (In Ruhig Fliessender Bewegung), based on "Saint Anthony's Prayer to the Fishes" from "Des Knaben Wunderhorn," rollicks along in three-quarter time. The ensuing "Urlicht" will stun first-time listeners to the performance. This movement sets a text by Klopstock about Christian conversion for contralto and orchestra. Fried finds distinct Jewish elements in the score, especially in the persistent solo violin accompaniment, akin to those in the Funeral March of the First Symphony. The conjunction of what sounds like a Yiddish lullaby in the violin with the contralto's articulation of Klopstock's devotional poem emphasizes the ecumenicity of Mahler's concept. To my mind, Fried's gesture markedly transforms the character of the symphony, forcing one to grasp it in a new way. The Fifth Movement Finale, with its offstage brass bands and large choruses, poses the severest challenge to the conditions under which Fried worked. Rarely, however, has the SHAPE of this movement been so clear. Recorded over many days and possibly in two separate locations, Fried's efforts defy circumstace by bringing amazing coherence and truth to Mahler's sprawling tableau. Even the grandiosity of it (of the symphony as a whole) remains in evidence. The closest subsequent thing to Fried's account is Otto Klemperer's Vienna performance (available on Vox) from 1951. Klemperer, like Fried, brought a modernistic idea to Mahler's score and never wallowed in the music. In addition to Fried's performance of the Second Symphony, this two-disc set also generously gives us several other items: *Jascha Horenstein's 1928 performance, with baritone Heinrich Rehkemper and the Berlin State opera Orchestra, of the "Kindertotenlieder," the earliest electrical recording of Mahler; *Soprano Grete Stuckgold's 1921 performance, with an unidentified orchestra, of Mahler's youthful "Ich Ging Mit Lust" and her 1915 performance, again with an unidentified orchestra, of "Wer Hat Dies Liedlein Erdacht" from "Des Knaben Wunderhorn"; *Soprano Lulu Mysz-Gmeiner's 1926 performance, with piano accompaniment, of the same song; *Baritone Heinrich Schlusnus' 1931 performances, with the Berlin State opera orchestra under Hermann Weigert, of "Rheinlegendchen" and of "Der Tambourg'sell," both from "Des Knaben Wunderhorn"; *Mezzo Sarah Charles-Cahier's 1930 performance, with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra under Selmar Meyrowitz, of "Ich bin der Welt Abhanden Gekommen," from "Lieder nach Rückert," and her 1930 performance, with the same accompaniment, of "Urlicht." -- All of which fascinates mightily and no doubt exhausts the archeo-discography of Mahler. (Rumors circulate, however, of a 1930 performance of the Fifth Symphony under Willem Mengelberg preserved on Dutch air-check platters. Get your hands on that, Naxos!) Horenstein's "Kindertotenlieder" is on a high level artistically and is finely recorded. In sum: A treasure-trove and a "must buy" for fans both of Mahler and of early ambitious recording." Ur-Mahler! Thomas F. Bertonneau | 03/14/2002 (5 out of 5 stars) "This is a review of the performance by Oskar Fried et al, which I know from its brief appearance on 33rpm vinyl (Pearl label, I think), circa 1985, and assume it sounds as good or better now on the Naxos CDs. Strangely the ancient acoustic recording never seemed to be much of a factor in my listening experience - the sense of the firey presence of the music itself blew away all other considerations. The music is just THERE, more immediate and urgent than on any other recorded - or live! - performance of the Resurrection Symphony I've experienced. Fried never gets in the way of the music, but if you're aware of him at all, it's because there's an incendiary intensity other conductors don't seem to muster up - the DIRECTNESS of the performance is self-effacing but in a way that only adds, paradoxically, to the character and quirkiness of the thing. Fried isn't breathing down your neck like some 'intense' conductors do; instead, he's blowing the flames of the music itself white-hot. Get it and give away all other versions - in this most sonic of symphonies, the technology doesn't matter at all. (Well, maybe it does... My enthusiasm for this recording should perhaps be taken with a grain of salt - I happen to love ALL acoustic recordings or orchestral music!)" Stunning Performance Jerold D. Kowalsky | NC | 02/18/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "The following is a review from Naxos web site-

Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911) Symphony No.2 'Resurrection' CD 1, Track 13: CD 2, Tracks 1-4) Born in Berlin on 1st August 1871, Oskar Fried exemplified the practical approach to music-making that had sustained the pre-eminence of the art-form in German-speaking countries over the previous century. Serving as a horn-player in Frankfurt's Palmgarten Orchestra from 1889, he soon moved to the Opernhaus and began composition lessons with Wagner's protégé Engelbert Humperdinck. A period as a freelance musician ended with his return to Berlin in 1898, to promote his own music, including, in 1901, a vocal setting of the Richard Dehemel poem Verklarte Nacht that had inspired Schoenberg two years before. In 1904 the cautiously post-Wagnerian tonal language of his cantata Das trunkene Lied found immediate favour. His career as a conductor received a similar boost when, a year later, he conducted Mahler's Second Symphony, the composer commenting that he could not have bettered the Scherzo in particular. Conducting Berlin's Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde from 1907, and the Bluthner-Orchester from 1908, Fried introduced further works of Mahler, as well as music by such contemporary composers as Schoenberg, Delius and Busoni. After 1913 he concentrated exclusively on conducting, where his combination of discipline and technical knowledge of the orchestral apparatus won wide admiration. His socialist and humanitarian convictions came to the fore when, in 1934, he left Germany for Tbilisi, taking over direction at the opera house there, and touring widely in the Soviet Union. He became a Soviet citizen in 1941, shortly before his death. To have recorded Mahler in 1924, before the acoustic process had been superseded by that of electrical recording, was a tough challenge for any recording team, but the Deutsche Grammophon company took the plunge with what, apart from the massive choral Eighth Symphony, was the most lavish of the symphonies. To what, if any, extent the limitations of the process inhibited Fried's approach to the Second Symphony is now impossible to judge, but the expressive freedom with which he controls the music, at the level of localised detail, between movements and across the work's almost 85-minute span, suggests that the personal conception that clearly impressed Mahler almost two decades before is substantially intact in the present recording. Fried sets a fast, incisive initial tempo for the opening Allegro maestoso, though an expressive use of rubato is soon in evidence, and he slackens skilfully for the second subject, opening up its idyllic vista with effortless poise. Some might consider Fried's marked ritardandos at climactic points too interventionist, though the explosive central development is potently handled, an object lesson in controlled spontaneity, despite the inevitable degree of overload in the recorded sound. While the string portarnenti at the reprise of the second subject may be a little mawkish for modem tastes, the funereal recessional that constitutes the coda is powerfully conceived, ominous to a degree that prepares for the settling of conflicts later in the symphony. Fried is clearly at home with the landler strains of the Andante moderato, maintaining continuity of tempo through the agitated episodes (superbly articulated strings here). There can be a thin dividing line between charm and schmaltz at such times in Mahler, and Fried nearly always gets the balance right. The cello counter- melody at the main theme's first reprise is delectably drawn, while the pizzicato strings and harp on its final return interlock with true precision. Love them or hate them, the violin portarnenti just before the close are a period detail worth savouring. The Scherzo sets off at a moderate, lilting pace, giving full rein to its subtle malevolence (what should be the strokes of birch-twigs against bass drum sound uncannily like hand-clapping - perhaps a problem of balance that was otherwise insurmountable back in 1924). The Trio breaks in with duly unwarranted triumph, Fried bringing out the trio-sonata interplay of its continuation, and easy sentiment of its slower section (what sounds like a bell replacing the triangle), though the even steadier pace he adopts for the scherzo's return makes tempo coordination a little approximate. The contralto Emmi Leisner makes a solemn impression in the radiant Urlicht setting, the richness of her lower register perhaps striking an anticipatory likeness to Kathleen Ferrier in the minds of many listeners. The gentle protestations of the second section arouse a heartfelt supplication. From the cataclysmic opening, Fried's conception of the Finale underlines the dramatic and dynamic extremes of this epic movement. He dispatches the initial episodes briskly, allowing atmosphere but little mystery, before the brass chorale emerges with restrained nobility, the climax creating a frisson of emotion. It is difficult after 77 years to appreciate just how difficult the articulation of the wrathful dance-of-death that follows must have been; the Berlin musicians convey the visceral quality of the music, though technical limitations bear witness to a struggle that only a conductor of Fried's experience could have brought off. Whether the 'last judgement' brass are in fact offstage, their placement at the margins of the sonic spectrum gives an impression of space and remoteness, complemented by the liquid tone of the solo flute. Klopstock's Resurrection Ode steals in raptly what sounds like a small but disciplined body of singers. Fried takes his time building to the climax, with such passages as the response between imploring contralto and pacifying soprano, the calmly assured Gertrud Bindernagel, bringing out the music's strongly human motivation. The peroration has none of the disingenuous theatrics that later generations would impose on Mahler's heaven-storming vision. For Fried, it was clearly a matter of conviction - no more and no less. Richard Whitehouse " |

Track Listings (13) - Disc #1

Track Listings (13) - Disc #1