Romantic Webern?

Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 01/24/2001

(4 out of 5 stars)

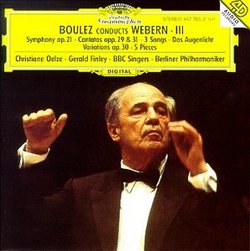

"Yes, yes. Anton Webern (1883-1945) took the implications of the so-called Second Viennese School to their most radical conclusions, but like his teacher Arnold Schoenberg and his fellow Schoenberg-student Alban Berg, Webern remained in touch with the Mahlerian late-Romanticism of his youth. Even the gnomic Symphony, Opus 21 (1927) looks back to Mahler and makes (I believe) specific references to the Ninth Symphony. Consider the opening gestures of Webern's Symphony: We hear harp, strings, and horn - the very same combination in evidence in the first movement of Mahler's valedictory D-Minor Symphony. This is fin-de-siècle hyper-Romanticism glimpsed through the refractory lens of post-Hapsburg modernism. Webern originally planned four movements for his Symphony but typically left only two for posterity. Had he fulfilled his plan, the existing movements would probably make more sense than they do and indeed their underlying Romanticism might be clearer. Herbert von Karajan played this music very slowly, drawing the Symphony out to over a quarter of an hour, almost as if to lend it Mahlerian proportions. Boulez, of course, takes it faster, but he grasps the link with Mahler more clearly than von Karajan. I once heard Boulez lead a rehearsal of Mahler's Ninth, and he lavished a great deal of attention to the timbres of the opening bars of the First Movement. He finds those same timbres in the corresponding bars of Webern's score. Does it seem odd to speak of Webern's Romanticism? But one only has to look at the texts that he chose for his vocal and choral music, especially the mystical poems by Hildegard Jone, with their Hölderlinian fondness for nocturnal nature-imagery and lightning-like revelations of Being, as in "Das Augenblick": "O sea of glances with its surf of tears... When the night of your eyelids silently descends / upon your depths, your waters wash / against those of death." Not even the "French" interpretations of Boulez can hide this. In fact, as they bring out the convergence of Webernian minimalism with Debussy's late style, also an outgrowth of Romanticism, they reinforce the intuition. This is the best Webern anthology ever, with crisp, luminous playing from the Berlin Philharmonic, beautifully recorded. Despite Boulez's reputation for uncompromising Cartesian coldness, what we have here is Webern the sensualist, Webern the mystic, Webern the devotee of Mahler. Of the Big Three atonalists, Webern is the least intimidating and Boulez makes for him a very user-friendly case."

Track Listings (21) - Disc #1

Track Listings (21) - Disc #1