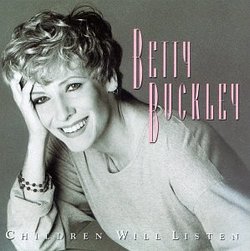

| All Artists: Betty Buckley Title: Children Will Listen Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 1 Label: Sterling Records Original Release Date: 5/3/1993 Re-Release Date: 7/15/1993 Genres: Pop, Broadway & Vocalists Styles: Oldies, Vocal Pop, Classic Vocalists, Musicals, Traditional Vocal Pop Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 757028100129, 757028100143 |

Search - Betty Buckley :: Children Will Listen

| Betty Buckley Children Will Listen Genres: Pop, Broadway & Vocalists

![header=[] body=[This CD is available to be requested as disc only.]](/images/attributes/disc.png?v=430e6b0a) ![header=[] body=[This CD is unavailable to be requested with the disc and back insert at this time.]](/images/attributes/greyed_disc_back.png?v=430e6b0a) ![header=[] body=[This CD is available to be requested with the disc and front insert.]](/images/attributes/disc_front.png?v=430e6b0a) ![header=[] body=[This CD is unavailable to be requested with the disc, front and back inserts at this time.]](/images/attributes/greyed_disc_front_back.png?v=430e6b0a) |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilarly Requested CDs

|

CD ReviewsIt's better in Buckley's world. This is your ticket. Ms. Mazeppa | Chicago, IL | 12/12/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "Word on the street is, Stephen Sondheim disapproves of how Betty Buckley tinkers with his melodies to make them her own. This makes me intensely uncomfortable, as I think of myself as unnaturally attached to both of them. Whenever I listen to Betty Buckley do her own thing to Stephen Sondheim's music, I can't help but feel a bit of regressive tension--like knowing that Mom and Dad are fighting again, and here I am in the middle, hiding out in my room, trying to tune out the arguing downstairs. Wondering what will become of us if they get divorced.

Now, devoted though I am to every single little bit of brilliance or effluvium that Sondheim emits, I have to say that Betty Buckley knows what the hell she's doing. Yep, I'm taking Mom's side. Even though she never sends me money. In general, I think Ms. Buckley's live recordings are her best (the bright, shiny exception being the newishly released, 1967). Among her studio recordings, Children Will Listen may be the best. It's not my sentimental favorite, but it really is a wonder. All of the songs are by theater composers and lyricists, and they reflect Buckley's famous sensibility for choosing and heightening the most vivid imagery in lyrics and melodies. Every song is a well-developed narrative or a brilliantly candid picture. Children Will Listen is story time, and it's wonderfully easy to get lost in it. So the result on this recording is a sort of musical transport to a dream world, oceans away, inside Buckley's head. Two songs into it, and you can't even see the shore anymore. That makes the third song, "Never Never Land," an especially prescient choice. It's as though she's making a point of teaching us the geography of where she's taken us. Generally, with Buckley's studio recordings, we see much more of jazz pianist and arranger Kenny Werner's collaborative hand in her style. And Children Will Listen, if I'm remembering right, is the first in those collaborations. One can argue that Werner sometimes seems to over-orchestrate, and one may find oneself muttering, "Just play the damn chord, Kenny". (Or maybe that's only my reaction to seeing Mom--I mean, Buckley--messing around with a guy who isn't Dad--I mean, Sondheim--and I should just deal with it in therapy.) As much as I feel allegiance to the original arrangements of some of these songs, I also find that the ones Buckley performs are often as good or better. Sometimes much better. "Meadowlark", for example, is a lovely story-ballad that works well enough as written. But I swear the original arrangement can seem long enough to require its own intermission. ("Really? The bird's not dead yet? I'm going out for another smoke. Signal me when the Sun God shows up.") Buckley and Werner resolved this problem by putting some kind of turbo-charged engine in the melody. It better matches the literary content of the lyrics, and it makes the tune more memorable. There's an important lesson here: You can respect a composer without necessarily reifying every single thing he or she does. In this instance, Buckley pays Stephen Schwartz great respect by doing something new and exciting with the song he created. Any songwriter should appreciate it when Betty Buckley develops a new translation of their music--in the same way that a good playwright should appreciate it when a talented director or actor finds new ways to draw out the meaning of their words. Fans of Broadway Buckley should be forewarned: When she and Werner do studio recordings together, there tends to be a lot less belting going on. The uncommon arrangements loan themselves to a softer, more contemplative impression. In fact, recognizing that Buckley's singing style is an indefinable fusion of jazz, country, traditional musical theater, and classic tin pan alley, it may be that Werner's unique backing is the glue that holds the whole composition of her recordings together. It may be that without the consistent flutter of his arrangements in the background, her mighty shifts and reversals might seem more disjointed across the recording as a whole. And for those of us who really enjoy getting all lathered up with that impossible range of hers, "Tell Me on a Sunday" is a dazzling exception here. The spine-tingling climax of the song is likely to be an adequate fix for those of us addicted to having our hair blown back by the full force of her voice. To me, it's a bonus that this recording contains three of the (precisely seven) Andrew Lloyd Webber songs that I like. That gesture alone should be considered a tremendous community service. By recording "Tell Me on a Sunday" and "Unexpected Song" here, she has saved us all untold dollars and hours contending with the cast album from Song and Dance. Indeed, if you've ever shelled out the cash and sat through the cast album from Song and Dance, you probably know you should send Betty Buckley a nice thank you note for saving you from ever having to do it again. I myself would have sent her a nice thank you note, but like I said, she never sends me money. For the record--and God forbid they should ever really divorce--but if Buckley and Sondheim ever do get into an actual fight, my money's on Buckley to knock the snot out of Sondheim. I'm just sayin'... " |

Track Listings (14) - Disc #1

Track Listings (14) - Disc #1