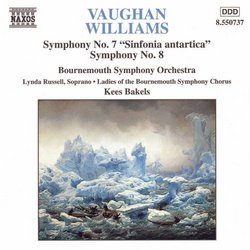

| All Artists: English Anonymous, Samuel Taylor [Poet] Coleridge, John Donne, Robert Falcon Scott, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Kees Bakels, Bournemouth Sinfonietta, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Christopher Dowie, Lynda Russell Title: Vaughan Williams: Symphonies Nos. 7 "Sinfonia antartica" & 8 Members Wishing: 2 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Release Date: 8/25/1998 Genres: Special Interest, Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 730099573726 |

Search - English Anonymous, Samuel Taylor [Poet] Coleridge, John Donne :: Vaughan Williams: Symphonies Nos. 7 "Sinfonia antartica" & 8

| English Anonymous, Samuel Taylor [Poet] Coleridge, John Donne Vaughan Williams: Symphonies Nos. 7 "Sinfonia antartica" & 8 Genres: Special Interest, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilarly Requested CDs

|

CD ReviewsBest "Sinfonia Antartica" Currently Available Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 10/23/2000 (4 out of 5 stars) "The classic recorded performance of Ralph Vaughan Williams' "Sinfonia Antartica" (completed 1952) is Sir Adrian Boult's on EMI from the mid-1960s; a slightly later performance on RCA led by André Previn boasted superior sound but misjudged by prefacing each movement with spoken versions of RVW's epigraphs. (Thus interrupting the musical continuity in a score that depends heavily on a seamless transition from one mood to another.) Bernard Haitink (also on EMI) issued an "Antartica" about fifteen years ago, very close to Boult's in merit, but - in this day of classical-music démorale - "no longer available." Haitink's countryman, Kees Bakels, has "burned" a CD cycle of the RVW symphonies for Naxos, with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, and one entry therein couples the Eighth with the "Antartica" (ordinally the Seventh). As James Day notes in his book on RVW, the "Antartica" calls on the largest orchestra that the composer ever stipulated, with parts for organ, wind-machine, an enormous percussion battery, and wordless soprano-solo with female choral vocalise. The "Antartica" shares with the "Pastoral" and the Sixth the evocation of inhuman nature and of human courage pitted (heroically but vainly) against such nature. Boult grasped this aspect of the work, but the limited capacity of mid-60s analogue recording took its toll on the realization of his understanding. (The vinyl pressings also posed an obstacle. I owned the American Angel pressing as well as an EMI import; neither struck me as adequate.) Bakels, like Boult, sees that this is a grim account, a genuine sequel to the tragic E-Minor Symphony of 1947. Notice how he takes the crescendi in the Prelude, with the great climax at 1.50: It's truly "majestic," as the score says it should be; the ensuing Lento, with prominent xylophone and wordless voices, sounds very icy and haunted indeed. The Scherzo presents the danger of sounding too comical; Bakels avoids this pitfall. Of the symphony's core, the "Landscape" (Third Movement), Bakels makes just the inhuman, implacable, frigid monster that RVW must have had in mind, although the organist (beginning at 8.30) does not achieve quite the hard-edged quality that I recall from Boult. The Eighth Symphony is a less monumental score, but possesses a playful seriousness all its own. The Finale can become a welter of sound, as it did unfortunately in the Boult/EMI; but here it sounds forth in all its polyphonic glory, with the tuned percussion caught with great definition by the engineers." A Tale of Two Eighths Karl Henning | Boston, MA | 07/30/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "I think many listeners (and reviewers) will focus more on the seventh symphony; so I leave the seventh to them, although I greatly enjoy this recording of the seventh, and am even modestly grateful that the recited superscriptions are included at the end, where they do not interrupt the sequence of the symphony itself.The Vaughan Williams eighth symphony exhibits a few interesting parallels with the eighth symphony of the composer whose oeuvre established the "rule of nine" in the writing of symphonies: Beethoven.Beethoven's Opus 93 strikes some listeners as both "a step backwards" from the rambunctious and expansive seventh (with its electrifying "double scherzo" and achingly intense theme-and-variations slow movement), and a mystification before the grandiose Opus 125. It is something of a look back towards Haydn; it is charming, and elegant, and seems to do entirely without the dramatic musical rhetoric of which Beethoven's third, fifth and seventh symphonies provide ample and potent illustration. It is the sort of thing which "musical progressivists" say we composers cannot do; you can almost hear the phrase spoken, "you can never go back."Yet, in his eighth symphony, Beethoven succeeds, marvelously and musically; he does, and does not, "go back." Vaughan Williams does something of the same, in his eighth. Even though Vaughan Williams' seventh was composed originally as film music, and then adapted as a symphony in his `cycle' (or perhaps because of this), the eighth seems like a deliberate step away from musical dramtization, and into the realm of abstract, `pure' music, a music which functions on its own, not driven by any extra-musical `program.'Now, the `point' to which Beethoven does and does not go back, is Haydn; the generation before, and a composer with whom Beethoven had taken lessons. The `point' to which Vaughan Williams does and does not go back, is musical Impressionism, and specifically Ravel. Vaughan Williams had taken some lessons with Ravel; and the `return to pure music' in the eighth is doubly apt here, as part of Ravel's Impressionism is a sort of `romantic neo-classicism' exemplified in "Le Tombeau de Couperin" and the piano concertos.That Vaughan Williams made his eighth with the Beethoven-parallel in mind, seems to me confirmed in the opening of the second movement. Vaughan Williams' all-winds scherzo begins with too much of a `metronomic' gesture for this to be coincidental. This parallel does not become burdensome, because the `metronomic piece' functions differently in the two eighth symphonies: it is the slow movement in the Beethoven Op. 93, followed by the lovely Menuet and Trio (good heavens! didn't Beethoven realize how passé this was?), while in Vaughan Williams' eighth it serves as a scherzo followed by a richly beautiful slow movement for strings alone (in timbral balance of the string-less scherzo).Where Vaughan Williams `does not go back' is, about two-thirds into the first movement, where, after some moments of trumpet-&-string doublings which seemed to evoke the sound-world of Prokofiev, the relatively smooth calm of most of the movement yields to the sort of orchestral menace normally associated with Shostakovich. This fury lasts but a moment, and gives way again to the idyllic calm of the opening material, but here is a musical point at which you wonder if it is really possible to `go back' ....The last movement of the Vaughan Williams' eighth is bright and resplendent. It is almost mis-labeled; `toccata' traditionally means a `touched' piece, a keyboard work with figurations more characteristic of two hands at a keyboard, rather than a large ensemble of single-line instruments. But Vaughan Williams has a history of adapting the idea of the Toccata, as in his Toccata Marziale for band; and my musicological quibble does not get in the way of the piece, which reminds me more of a jubilant carillon.--Karl" Unbelievable Sound Quality Doc Sarvis | 03/17/2002 (5 out of 5 stars) "The "Antarctica Symphony" portion of this disk has been called "the best digital recording ever made", and is often recommended for use as a demonstration disk on high-end audio equipment. One listen and you'll understand why...this is truly a sonic marvel.Not a bad accomplishment for budget-price label Naxos!"

|

Track Listings (14) - Disc #1

Track Listings (14) - Disc #1