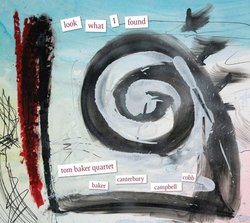

| All Artists: The Tom Baker Quartet Title: Look What I Found Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Present Sounds Recordings Original Release Date: 12/26/2006 Re-Release Date: 1/1/2007 Genre: Jazz Style: Avant Garde & Free Jazz Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 634479412219 |

Search - The Tom Baker Quartet :: Look What I Found

| The Tom Baker Quartet Look What I Found Genre: Jazz

From Earshot Jazz Magazine, January 2007 The opening of the Tom Baker Quartet's debut CD, Look What I Found, may be indicative of the guitar-playing bandleader's life these days. He starts the album with "Swampled" and a ... more » |

Larger Image |

CD Details

Synopsis

Album Description

From Earshot Jazz Magazine, January 2007 The opening of the Tom Baker Quartet's debut CD, Look What I Found, may be indicative of the guitar-playing bandleader's life these days. He starts the album with "Swampled" and a choice three-note mid-range phrase that immediately gets battered by drummer Greg Campbell's bass drum and an interjecting cymbal crash and snare-drum snap. Then comes a nudge from Jesse Canterbury's clarinet, underneath which Brian Cobb's bass presses. A give-and-take ensues for more than a minute, as if Baker, a consummate guitar-slinger for sure, can't (or won't) outrun his band. He digs them too much, their jostling, their sense of how a group thinks. In turn, they create a woodsy vibe, all rich colors with a swirling warmth. "[T]hese guys are so perfectly suited to this music," Baker says in response to a question about how someone assembles a clarinet-guitar-bass-drums quartet. Yes, he loves "the colors of clarinet and guitar," but even more, Baker enthuses over playing with "world-class improvisers who are well versed in contemporary classical music, world music, and traditional jazz." And therein lies an important part of his own story: He's steeped in academia as a performer and composer. You could surmise, given Baker's past, that he'd be writing post-symphonic tone-rows - not that there's anything undignified in that. He's living, though, outside the academy now, thriving on playing and composing and thinking about music. What you hear on Look What I Found, are ten tracks that indulge improvisation while living within tunes that have distinct rhythmic tilts and tugs. Coming from someone whose recorded output includes an experimental opera and two solo fretless-guitar albums, the Tom Baker Quartet sounds brilliantly collective: It's a band, of course, riffing off and playing with each other. It's also a collective in that it freely weaves together composition and improvisation. Or, as Baker puts it: "The line between notated complexity and improvised complexity seems very, very thin to me, and the extra energy or spirit that improvisation brings to the table is something I've always tried to use as a composer." While a distinct success on Look, Baker's past efforts at commingling improvisation and composition have led to strange occasions: "I wrote a piece for four improvisers when I was in Grad school," he says, "using a graphic notation that mapped out only the density/intensity/activity over time. The piece was indeterminate in length, and the energy of the improvisation was exactly what I had hoped." Even so, Baker knows that such lofty conceptual objectives can be misapprehended. "The piece," he says, "was not very well received by my colleagues and professors, even though the players really liked it and I thought it worked well." Rather than consider himself chastened, Baker pushed ahead with what he calls the "merge" of improvisation and composition. "Flow is the most important thing," he says. Baker spent the last 13 years teaching in the University of Washington's music composition/theory department, a place where music can be composed, performed, and put to bed with barely any notice outside the academy. Although he didn't leave the UW in order to pursue a different musical path as such, the change has reverberations. "For right now," he notes, "I am trying to compose and perform as much as I can and trying to be as honest as I can about the music I am making. Crafting a musical life." That objective Baker learned in full blossom while a resident artist at Florida's Atlantic Center for the Arts in 2005. "I had the transformative experience of working with Henry Threadgill, and it was one of the most thrilling and important musical experiences of my life." A famously maverick composer, Threadgill insisted first he wasn't a teacher, and, Baker notes, "he proceeded to be the best teacher once could ask for." As with so many great teachers, Threadgill's lessons exceeded their stated purpose. He covered music: "Flow, intervallic consistency, counterpoint, orchestration. All of it," says Baker. And then, "Henry would come in talking about Stravinsky one day and Dizzy the next, and then on to world politics and the outdated mode of transportation that is airline travel. And all of it with purpose. With great intention. That is Henry's real gift. Everything he does is intentional and has a purpose, even when it isn't clear right at the outset. Intention is everything." Detailing the experience, Baker clearly slips into its intrinsic rhythms, its creative energies. Those are the undercurrents for all that he has done since. The apogee of the post-Threadgill activity is Look What I Found. The album bears the marks of Threadgill, the halting rhythms, the wide-open spaces in the middle of a tune - big enough to picnic in but never a misuse of territory, and the sibling focal points of tonalities and tunefulness. Woods are a huge part here, with Baker reveling in his guitar's rich middle and the clarinet floating and weaving like a closely huddled fog. Campbell's percussion is rumbly, not snappy, and when prone toward the clang of cymbals almost always opting for bell-like tones. Brian Cobb's bass has an acoustic bound that's a pontoon, everything else atop it. At one point in our exchanges, Baker points out: "I am always inspired by the music of Charles Ives and Morton Feldman. And if I need to refocus, Ornette is always there to get things realigned." Conjuring Ornette Coleman as a force for re-alignment says a lot about the sound here, because Baker certainly has embraced a version of Coleman's harmolodics. These tunes don't speed like "Blues Connotation" or slow way, way down like "Lonely Woman," but they do have an internal spring-loadedness that's electrifying. The ideal place to craft a musical life is, of course, the stage. And that's an omnipresent subject with musicians. "You play every chance you get," Baker says, "and you try to play gigs that fit the kind of music you are making." Audiences come and go, though: "Seattle has lost a lot of great venues for experimental music in the past several years or so (the Penny Cafe, the OK Hotel, the Speakeasy). There are new ones, and there will always be cycles for a scene of this size." Whether the gigs are plentiful or not in the present moment, Baker's an optimist: "I have a hunch we are on an upswing, though. I think that people are starting to come back out for live music experiences, and it will continue to get better." Now if only we could get that outmoded airline travel thing fixed for Henry Threadgill. --Andrew Bartlett

Similar CDs

| Various Artists Original Comedy Genres: Special Interest, Pop Label: EMI Import | |

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1