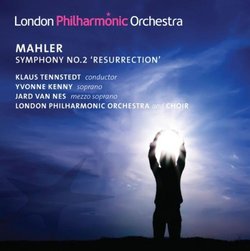

| All Artists: Mahler, Van Nes, Lpo, Tennstedt Title: Symphony No 2 Resurrection Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: LONDON PHILHARMONIC Original Release Date: 1/1/2010 Re-Release Date: 3/30/2010 Genre: Classical Style: Symphonies Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 854990001444 |

Search - Mahler, Van Nes, Lpo :: Symphony No 2 Resurrection

| Mahler, Van Nes, Lpo Symphony No 2 Resurrection Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsAn exceptional Resurrection MartinP | Nijmegen, The Netherlands | 05/15/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "Usually, I'm not one for 'legendary recordings'. I've heard one too many of those where the reputation was rather more spectacular than the actual music-making. Myth-making is rife among classical music aficionado's... I am also somewhat puzzled by the posthumous veneration for Klaus Tennstedt, whose 'official' Mahler cycle on EMI had a generally tepid reception, rightly so in my opinion, excepting, of course, his justly famous Eighth. Years after his untimely death the BBC unearthed a recording of Mahler's Seventh that was released in their dangerously named 'legendary recordings' series and became something of an 'insiders tip', though on listening I found very little of note in it. But this recording of the mighty Resurrection is a different story altogether. It is conceived on the most grandiose scale imaginable, but weds sheer majesty to depth of feeling in an unprecedented way. Rubato is at times extreme, but while I found it definitely eccentric on one or two occasions, in general it is thoroughly musical and well-considered. Indeed, the great strength of this reading is that it gives you the feeling that every note and every passage was deeply and thoroughly considered. There is no padding, there are no dull spots, and while every detail is spot-on, the slow build-up to the soaring climax is never lost from view either. All this is captured in sound of the highest quality, rich, transparent, detailed and powerful, and while recorded live there is hardly an audible trace of the audience on either disc. They must have been awe-struck. It is hard to imagine that this is a one-off concert recording. The first movement is taken in a deliberate tempo that fits its maestoso character very well. In the first half Tennstedt does go against Mahler's tempo instructions a few times in a way I found slightly irritating (as at #6, where he starts a huge ritenuto several bars before Mahler wants it, and has come to a virtual standstill by the time he arrives at 'Beruhigend', where the slow-down should actually start). But all is well after that. The slow tempo for the second theme, combined with the gorgeous playing all round, results in passages of sheer magic. The effect is much enhanced by the stunning transparency of the recording. You can actually hear that low bass note in the horn at #9, tingeing the atmosphere with darkness. Many such captivating details grab the ear, like the true spiccato of the violins after #16, or the way the descending bass line remains audible despite all the ear-splitting force of the great, grinding climax just before the reprise. The second movement is not allowed to be the fairly light-footed intermezzo we usually hear. Tennstedt gives it weight by playing it very slow, with lots of subtle (or not so subtle) rubato. Andrew Davis did this movement with as much rubato, but while in his case it just turned the music into nauseating chewing gum, with Tennstedt it works. His rubato is well thought out and thoroughly controlled. The playing is again exquisite, and at this tempo the passage with the staccato triplets becomes surprisingly ominous. In all, this slow Ländler is very much of a piece with the rest of the symphony. The Scherzo is taken at a nice, flowing pace and has irony and sarcasm aplenty, maybe going a little over the top even in the violins, but that's much to be preferred over the many underplayed renderings this piece has suffered. At #40 I was struck by the beautiful crescendo-decrescendo effects in the trumpet, and in general by the awesomely rich presence of the bass drum. The great climax is realized spectacularly, with fantastically braying horns. Next, Jard van Nes gives a touching rendering of Urlicht. In the Netherlands her name used to be more or less synonymous with Mahler, so it is good to hear her sing one of her signature pieces for an international audience in the context of such a magnificent performance. Her dark voice is maybe more easily associated with the Mitternachtslied from the Third, but actually fits very well with Tennstedt's brooding, dark vision of the Second. The opening of the Finale is as grandiose as might be expected by now, and is richly coloured by the well-caught sounds of tam-tam and bass drum. At #6, where the first, piano statement of the resurrection theme sounds, Tennstedt and his players again weave a web of magic, the long held notes marked ^ very well observed. Quite breath-taking. It is a pity that thereafter the distant horn seems to be in a bit of trouble, but it is a minor quibble. Again in this great patchwork of a movement the listener is struck by how lovingly every passage is moulded, how nothing is indifferent. The great percussion crescendo, so often underplayed, is given all it's worth, after which Tennstedt tears into the marching episode at white heat. But even then attention to detail never wavers, as at a few bars after #18, where we get to hear the double-stopped sixteenths from the violas, a marvellous effect that I hadn't noticed ever before. The strange little marching band at #22 has more presence than in most recordings, and rightly so, even though it's a pity we don't hear it crash into the main ensemble the way Mahler wanted - an effect rather difficult to stage manage in concert. The big crisis before the entrance of the chorus is absolutely dumbfounding, horns again soaring magnificently over the turmoil. It provides a heart-rending contrast with the quiet loveliness of the ensuing episode, where the playing is marvellously expressive. Unfortunately the great fanfares of the Fernorchester sound a little thin and do not quite come off without accidents, but the heart-stopping entry of the chorus will soon make you forget that. From here pp and ppp are doggedly observed creating a very inward, mysterious atmosphere. Only at the very end are the massed forces allowed to surge, and give us simply the most blazing final Resurrection chorus ever heard on disc, resplendent with thunderous organ. Had there been audible bells as well, perfection would have been attained - but I suppose that is too much to ask in this imperfect world. I've never seen the point of including applause on a CD, but in this case the thunderous ovation following the final chord is fitting and very well-deserved. A CD no lover of Mahler can be without. " Tennstedt's live "Resurrection" rises to greatness Santa Fe Listener | Santa Fe, NM USA | 04/01/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "Once Mahler ceased to be a rarity, it was time for the next phase, in which conductors could begin to more deeply interpret his music. Sadly, few have risen to the challenge. Even provincial orchestras can negotiate the once formidable Mahler Second, yet it's hard to think of a recording as inspired as the one from Bernstein and the NY Phil. recorded almost fifty years ago. Here is a magnificent exception, however, a live reading from 1989 at London's Royal Festival Hall. Tennstedt was a great original -- one of the last -- and his every gesture is full of spontaneous feeling. Nothing here is standard. Tennstedt is so comfortable in Mahler's world that he phrases with absolute freedom, telling us a story we haven't heard before, even though the 'Resurrection' Sym. is now as familiar as the Beethoven Fifth.

Literalists won't be happy -- tempos fluctuate by the moment, as do dynamics. It takes a masterful hand not to turn this into a free-for-all. Instead, Tennstedt keeps you waiting in fascination for his next mood. In general, many moments are tender and reflective, so this isn't a reading for thrills, but how fresh the first movement sounds, liberated from its usual role as a lugubrious funeral march. Tennstedt finds something new around every corner. The devoted London Phil. plays with much more freedom than on their EMI studio recording of this work under Tennstedt, and despite Royal Festival Hall's weak bass response, the recording is close up, clear and detailed, with no obvious flaws. I'm tempted to say nothing more and leave the whole recording as a surprise. A few impressions will suffice. The minuet in the second movement is taken quite deliberately; in place of the usual light respite from the impetuous drama of the exhausting first movement, Tennstedt seems to sink into a touching melancholy. The later eruption becomes quite heart-rending. As for the Scherzo, I never expected to hear one better than Bernstein's, since he caught its droll, biting, and whimsical sides so well. Tennstedt is more meticulous and, I suppose, innocently good-natured. But he captures Mahler's unsurpassed orchestration so perfectly that the sunny mood isn't simple; it's highly colorful. Mezzo Jard Van Ness was an experienced soloist in the Mahler Second, and against the background of Tennstedt's broad, moving accompaniment, she makes "Urlicht" memorable, if not quite the unforgettable experience offered by Janet Baker and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. At this point, many listeners expect the volcanic outpouring of Solti in his groundbreaking Mahler Second with the London Sym. on Deca. Blessedly, Tennstedt finds another way, one not so blatant and extroverted -- this symphony is a soul's progress, not a cinematic depiction of apocalypse. Mystery is called for, and I've never heard that achieved so well as here. The "Tennstedt effect," as the note writer calls it, has set in fully; he evokes hushed awe where others lapse into bombast. The excellent chorus enters on a true pianissimo, drawn out forever -- I doubt that anyone in the hall could draw a breath. Yvonne Kenny rises flawlessly from the shimmer of the chorus, and only then does Tennstedt begin the inexorable unfolding of heavenly grandeur. This is interpretation of the rarest kind, an unforgettable experience even through the impersonal medium of recordings. I have no hesitation calling it the greatest Mahler Second in decades. One has the uncanny feeling that the music is being created before one's eyes." |

Track Listings (1) - Disc #1

Track Listings (1) - Disc #1