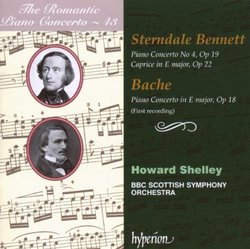

| All Artists: William Sterndale Bennett, F. Edward Bache, Howard Shelley, Glasgow BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Title: Sterndale Bennett: Piano Concerto No. 4; Caprice in E major; Bache: Piano Concerto Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Hyperion UK Original Release Date: 1/1/2007 Re-Release Date: 10/9/2007 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Instruments, Keyboard, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 034571175959 |

Search - William Sterndale Bennett, F. Edward Bache, Howard Shelley :: Sterndale Bennett: Piano Concerto No. 4; Caprice in E major; Bache: Piano Concerto

| William Sterndale Bennett, F. Edward Bache, Howard Shelley Sterndale Bennett: Piano Concerto No. 4; Caprice in E major; Bache: Piano Concerto Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsDelightful David Saemann | 04/02/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "As this wonderful CD demonstrates, there was much going on in the middle of the 19th Century that is not reflected in today's standard repertoire. The two works by William Sterndale Bennett are tuneful, beautifully constructed, and full of bravura passages for the soloist. Howard Shelley demonstrates once again that he is one of our more treasurable artists. Not only is his piano playing vivid and exciting, but somehow he manages to direct the orchestra at the same time in elegant but full-bodied accompaniments. Leader Elizabeth Layton probably deserves some of the credit for the latter. As for the Bache concerto, it is really wonderful, inventive and exciting with soaring melodies. Since Bache died of tuberculosis at age 25, he is one of the tantalizing "what ifs" of music history. It is hard to believe that the Bache is a first recording. The sound engineering of this CD is full-bodied and well-balanced, if perhaps lacking the last word in presence. One only can hope, forlornly, that other pianists will take up these pieces." Scintillating performances; unfortunately the music is dull G.D. | Norway | 08/25/2009 (3 out of 5 stars) ""I would challenge anyone to listen to this CD and still insist that in the first half of the nineteenth century Great Britain was a `Land without Music'" writes John France of International MusicWeb. Well, I am not going to insist on anything, but if this disc is the best case that can be made against that common conception, I don't hold up much hope (regardless of how desperately France and others will run the `prejudice' gambit). William Sterndale Bennett (1816-1875) is surely a fine craftsman; the material is skillfully handled and he does have a good sense of form. Unfortunately the two pieces that represent him here are desperately dull.

As widespread opinion will have it, the influence of Mendelssohn is strong. But Mendelssohn was a somewhat uneven composer, and what Bennett has taken from him must surely have been the more conventional, uninspired parts. That said, Mendelssohn's isn't the name that first springs to mind; there is, in fact, little here that takes us far beyond Mozart - Bennett also admitted his own his conservativeness in that respect - although one finds touches of composers such as Moscheles as well. Now, that need admittedly not be bad in itself. The problem is rather what Bennett manages to do - or doesn't manage to do - with those influences and the few non-derivative ideas of his own he adds to the mix. The fourth piano concerto is even usually considered to be his best. It is an early work, dating from 1838 (apparently most of his music was written early in life). The first movement has some poetic touches, but the material is undistinguished and immediately forgettable. The central Barcarolle, on the other hand, is actually rather appealing, with some nicely shaped melodies subjected to light and elegant treatment. The final presto agitato never manages to take flight, however, and what is apparently supposed to be a glitteringly brilliant wild run sounds merely meandering and persistently earth-bound. The firmly Victorian Caprice, from 1836 (probably), is a more modest work and is, despite failure to catch one's interest or stay in one's memory, perhaps worth hearing at least once. I found the piano concerto of Francis Edward Bache to be more engaging. Bache (1833-1858) is sometimes perceived as one of those would-have-beens whose early promise was cut short by early death. I don't know. The music certainly shows talent and, occasionally, inspiration, but little originality and frankly no signs of a great composer in formation. Still, the ambitious piano concerto is pleasant enough, with quite a lot of charm, some nice thematic material and a skillfully wrought solo part. Mendelssohn is still an audible influence, but at least Bache manages to assimilate his influences into an engaging and at times - in the faster parts - perhaps even sparkling musical language. I have no complaints whatsoever regarding the performances. I don't think these works could receive more convincing advocacy than they receive from Howard Shelley and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, so when they still fail to convince the blame can hardly be assigned to the performances. In addition, everything else about this issue is superb; the sound quality is warmly spacious and brilliantly clear, the booklet informative and the presentation appealing. That, in addition to the historical interest, does perhaps make this a worthwhile issue, at least for those with a special taste for music of this era. And maybe some people will get more out of this issue than I did, but my final verdict cannot be otherwise than that this is one disc I probably won't return to in a long time." |

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1