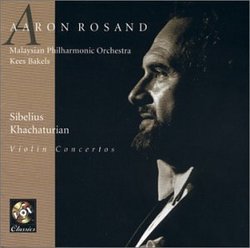

| All Artists: Aram Khachaturian, Jean Sibelius, Kees Bakels, Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra Title: Sibelius, Khachaturian: Violin Concertos Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Vox (Classical) Release Date: 1/2/2001 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Instruments, Strings Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 047163790423 |

Search - Aram Khachaturian, Jean Sibelius, Kees Bakels :: Sibelius, Khachaturian: Violin Concertos

| Aram Khachaturian, Jean Sibelius, Kees Bakels Sibelius, Khachaturian: Violin Concertos Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsFanfare Magazine March/April 2001 Robert Maxham | Lynchburg, VA USA | 03/15/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "At an age at which Heifetz was contemplating retirement and Elman should have been, Aaron Rosand issued a commanding, authoritative recording of the Beethoven and Brahms Concertos (Vox VXP 7902, 22:4). Now, two years later, he has paired a craggy Sibelius with a kinetic Khachaturian, evincing full command of the works' power and exoticism, respectively. Only Milstein and perhaps Shumsky could boast such violinistic longevity (consider, for example, Elman's senescent and deliberate, if genial, reading of Khachaturian's Concerto from his 69th year, which hardly approaches Rosand's in technical assurance).Aaron Rosand's sound has varied little through his recorded career: it's robust and rugged, with a mild acidity that, highlighting almost every note, sets his tone apart from the blander, smoother, and smaller timbres of younger players (and almost every player now is younger). That sound owes a share of its individuality, of course, to the magnificent Kochanski Guarneri of 1741, which, as Rosand says, has been his voice for 43 years; but it's the result of a complex interaction between that violin and a master who undoubtedly could, as Heifetz did, project his individuality through any instrument (having heard Rosand try violins at William Moennig and Son's shop in Philadelphia, I can confirm the stability of his sound, at least in that setting, across platforms). But far from merely luxuriating in his recognizable tone, Rosand laces whatever he performs with strong fiber, an essential toughness that reveals itself as tellingly in lesser-known works like Joachim's Hungarian (Vox CDX 5102) and Arensky's (Vox 7211, 23:4) Concertos, which were for a long time almost his private domain, as in masterworks like Tchaikovsky's Concerto (again Vox 7211) or Bach's Solo Sonatas and Partitas (Vox VXP2 7901, 22:2).Rosand's waves of inspiration lash against granite in the Sibelius Concerto's first movement; he sings warmly in its second (the trace of acid in his tone ensuring that the music won't cloy) and slashes masterfully through the finale's craggy darkness-all the while demonstrating the durability of his tonal and stylistic personality through his 71st year. If Khachaturian's Concerto doesn't provide him as many such opportunities for discovery, he and conductor Kees Bakels engage in a cogent dialogue in the first movement's middle section, and he brings a jazzy cheek to the cadenza's closing passages. The second movement's sprawl may be due more to its materials than its performers; but, in any case, Rosand and Bakels come to life again in the alternately sprightly and brassy finale.The decline in influence of Heifetz's benchmark recordings has freed violinists to invest Sibelius's Concerto with fresh insight; and Rosand's new performance joins recent ones by Maxim Vengerov and Joshua Bell in transfusing new personality into the work. And whether or not Mozart's Emperor would judge that Khachaturian's Concerto has too many notes, Rosand plays each of them with twangy zest. That sizzle sets him apart from violinists like Oscar Shumsky, who, despite-or because of-their unvarnished merit, appeal more to colleagues than to general audiences. By comparison, Rosand's a demagogue, rotund in oratory and resonant in vocal quality. Vox's engineers have provided depth and clarity appropriate to Sibelius' Concerto (but with a close focus on the soloist) and have captured reasonably well Khachaturian's dollops of sound, generously dished out by Bakels and the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra.All lovers of the violin, and general listeners as well, may count themselves fortunate that Rosand's artistry isn't available only in reissue, and that his playing maintains, or exceeds, a level familiar from his recordings a generation ago. Strongly recommended.Robert Maxham" Temperament and Tone Robert J. Sullivan Jr. | Chicago, IL USA | 11/05/2001 (4 out of 5 stars) "Though all the usual attributes of a Rosand performance are present --- technique, temperament, and tone --- I can't say these recordings rank in the top third of his many recorded performances. Rosand has been consistently let down by his orchestral partners. The Sibelius, in particular, lacks heft here. The bristling utterances that should reinforce the violin's dramatic statements do not excite; I felt an overall lack of involvement from the orchestra. The Sibelius is rife with passionate themes, and when a first-class string section such as the Philadelphia carries them, you feel it in the gut. If Dylana Jensen could get Ormandy (what a partner!) as a virtual unknown, then where does that leave Mr. Rosand? It's sad.At this stage in his career, Rosand cannot quite generate the whirlwind of sound that placed him in the forefront of his generation, so it is all the more important that he have a strong ally. The Khachaturian comes through much better; the Malaysian group has the necessary mechanical precision to bring it off and the recording is generous with the color.In summary, the Sibelius is worth it only if you want to hear Rosand's ideas on the solo part." Rosand at his best-again Rolf K. Liebergesell | Darien, Connecticut United States | 12/10/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "No superlatives can do justice to the music-making of Aaron Rosand. Here are more examples: The somewhat somber Sibelius embellished with Rosand's usual romantic touches - simply superb,

and an incredible performance of the seldom-heard Khachaturian." |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1