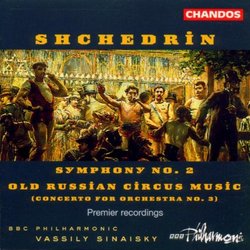

| All Artists: Rodion Shchedrin, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Title: Shchedrin: Old Russian Circus Music/Symphony No.2 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Chandos Original Release Date: 1/1/1997 Re-Release Date: 9/16/1997 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 095115955222 |

Search - Rodion Shchedrin, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra :: Shchedrin: Old Russian Circus Music/Symphony No.2

| Rodion Shchedrin, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Shchedrin: Old Russian Circus Music/Symphony No.2 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsThe Progeny of Shostakovich's Fourth Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 11/12/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "Thanks to the massively vindicated Solomon Volkov, we now understand Dmitri Shostakovich as the great artist-dissident of Soviet totalitarianism. Other "Soviet" composers must be measured not only artistically but ethically against DSCH. By this criterion Rodion Shchedrin (born 1932) earns ambiguous marks. He often tested the limits of "socialist-realist" conventions in music, only regularly (in the 1960s and 70s) to reaffirm the politically correct line. Thus, in his Piano Concerto No. 2 (1964), he explored expressionistic, even atonal, means; but in his cantata "Lenin Lives in the People's Heart" (1969), he set a Communist-Orthodox text which could have had no other purpose than to please Party officialdom. Vassily Sinaisky's CD of Shchedrin on Chandos offers two works that illustrate the composer's ambiguous status. The minor work is "Old Russian Circus Music: Concerto for Orchestra No. 3" (1989), maybe at twenty-four minutes not so minor. Drawing on traditional popular tunes associated with the traveling carnivals of pre-Soviet Russia, it manages to accord with the "socialist-realist" prescription that concert-music should establish its basis in the melodies of "the people." But its Stravinskian treatment of the old tunes thumbs its nose at Khrennikovian correctness. You might say that Shchedrin cleverly has it both ways in this ingenious and ingratiating work, which however belongs to the period of Glasnost under Mikhail Gorbachëv, when the threat of anathema no longer existed. The large-scale Symphony No. 2, or "Twenty-Four Preludes for Orchestra" (1964), is another matter entirely. Its intrinsic qualities and its context together press one toward the use of the word "courageous." If DSCH's Fourth Symphony (1934), suppressed for nearly thirty years after being withdrawn short of its première and heard for the first time only in 1962, has a successor, it might well be Shchedrin's Second. Shchedrin groups the twenty-four preludes into five substantial movements. He has cited conditions in the USSR during World War II as the inspiration for his musical imagery: Soldiers on the march, dreadful news of battles against the invader, air raids, domestic fear under Stalin's regime. Shchedrin was eight when Hitler sent the Wehrmacht into Russia and remembers the war from a child's perspective. (Not, that is, from an ideological perspective, but as a sensorium, quite beyond ideology. This is already pure heterodoxy when considered from a Marxist-Leninist viewpoint.) The symphony employs a modernist language deriving from Shostakovich's experimental period; the Fourth Symphony appears to be uppermost in Shchedrin's thoughts while he is conscious also of works like the Second Symphony and the Third, with their conspicuous onomatopoeic devices. (Factory whistles, military percussion.) Massive orchestral polyphony forms the typical mode of this style, with marchlike themes in Hindemithian counterpoint chugging along in machine-fashion and abrupt changes of tempo and mood. A huge orchestra enables Shchedrin to create a constantly shifting texture of unusual instrumental combinations. Half-remembered songs and tunes drift by. Moments of eerie desolation break up the parade-ground episodes. Once upon a time, you could consult a Melodiya LP of this score, also briefly available as a Westiminster-ABC budget-line LP and oh-so-fleetingly as an imported Melodiya CD. The Chandos recording from 1997 improves incalculably on the older playback version, with the BBC Philharmonic giving an idiomatic performance. Shchedrin's reputation rests on his strings-and-percussion adaptation of Bizet's "Carmen." One can understand that work's popularity. The serious Shchedrin is in the Second Symphony. Call this a "must" for anyone interested in the post-Shostakovich succesion in Soviet music."

|

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1