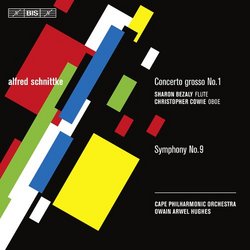

| All Artists: Alfred Schnittke, Owain Arwel Hughes, Grant Brasler, Cape Philharmonic Orchestra, Albert Combrink Title: Schnittke: Concerto grosso No. 1; Symphony No. 9 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Bis Original Release Date: 1/1/2009 Re-Release Date: 7/28/2009 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 675754017477 |

Search - Alfred Schnittke, Owain Arwel Hughes, Grant Brasler :: Schnittke: Concerto grosso No. 1; Symphony No. 9

| Alfred Schnittke, Owain Arwel Hughes, Grant Brasler Schnittke: Concerto grosso No. 1; Symphony No. 9 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsThe last word on Schnittke's Ninth hasn't been spoken ... Philippe Vandenbroeck | HEVERLEE, BELGIUM | 10/30/2009 (3 out of 5 stars) "We had to wait for a long time to hear Schnittke's last and Ninth symphony and now two recordings have been issued in short succession. Some context is in order to position this work in the composer's oeuvre. In 1994, four years before his death, Schnittke suffered a stroke which led to a partial paralysis. Disposing of his left hand only he worked on his last symphony. The status of the resulting score, however, is unclear. It appears that Schnittke's manuscript contained many indecipherable, ambiguous passages and needed reworking before it could be performed. Hence, the score is referred to as a "reconstruction" by a fellow Russian composer, Alexander Raskatov. That's the short version of a more complex story which still leaves many questions open. First, there are sources that claim that the symphony was left incomplete by Schnittke, meaning that we are dealing with a completion (or, perhaps, a "performing version" à la Mahler 10) rather than a reconstruction. If the three original movements were not fragment "but clearly conceived and committed to paper with admirable completeness" why did Raskatov take four years to put the manuscript into playable form? What is the status of the Rozhdestvensky version (mentioned in the liner notes by Alexander Ivashkin accompanying the present BIS recording) which was prepared in a short space of time but allegedly dismissed by Schnittke in the last months of his life? What is the relationship between the Ninth and "Nunc Dimittis" - a vocal composition written by Raskatov in conjunction with his work on the Schnittke score? Was it really meant as an "addition", a vocal finale as it were, or is there no formal link between the two works? These are the ambiguities presently swirling around Schnittke's enigmatic valedictory symphony. Anyway, the premiere recording (performed by the Dresdner Philarmonie conducted by Dennis Russell Davies, on ECM) revealed a work that is not immediately easy on the ear. Extremely sober and laconic, it connects to the concentrated minimalism of the Sixth and Seventh symphonies rather than to the theatrical and cinematographic intensity of many of his other works. The Ninth has been conceived as a succession of three movements, the first of which (labelled Andante by Raskatov; originally it came without tempo indication) is longer than the two following movements together (Moderato and Presto, respectively). What was striking about the ECM recording is the relatively slight differences in tempo between these movements. Russell Davies opted for a gradual quickening of the pulse rather than for a set of conspicuously contrasting movements. This feature combined with the textural, harmonic and melodic evenness of the musical material made for a rather challenging (some would even say "bland") listening experience. However, a Canadian listener (and Amazon reviewer) conceived of a rather brilliant idea based on a careful study of the score: by way of experiment he re-tempoed the Russell Davies version, expanding the first movement by 20% (obviously whilst respecting the pitch) making it 24 minutes long, keeping the second movement as it is and contracting the last movement by 19% to a proper Presto. The resulting "re-tempoed" version indeed seems to make much more sense. Suddenly things fall into place and as a listener one can start to navigate this complex symphonic landscape. (Admittedly, by re-tempo-ing the reconstructed version we are adding yet another layer of ambiguity to this already puzzling work.) So to what extent does the BIS recording, with the Cape Philarmonic Orchestra under Owain Arwel Hughes help us to shed further light on the Ninth? Well, the recording timings for the three movements already tell us a good deal of the story. Arwel Hughes opts for an even faster first movement (18'03) compared to Russell Davies (19'56; so very much the opposite of the re-tempoed version which comes in at 23'43). He sticks to a very similar tempo for the Moderato (7'57 compared to 8'24) and opts for a significantly faster Presto (7'01 vs 8'31). Hence, Arwel Hughes seems to steer a course that conflicts with Raskatov's intentions (which allegedly mirror those of Schnittke's widow Irina who thought the symphony ought to embody "an accelerando of time"). In the South African interpretation we have a more traditional relationship between the tempoes with a fast opening movement (sounding rather like an Allegro, or at least a Moderato, certainly not like an Andante), a slower second movement and final Presto. Just to illustrate the enormous differences between the BIS recording and the re-tempoed version: the first paragraph of the opening movement, consisting of three repeats of a questioning motif on the strings (the first two of which are separated from the third by a long Luftpause) takes a full minutes in the latter whilst 38" suffice for the Cape Town forces. Clearly we are in for a very different listening experience! Apart from the tempo there is another feature that strikes me in the BIS recording which is that the wind and brass solos are brought sharper into relief, making the work sound more like a concerto grosso, compared to the ECM version which is more unabashedly "symphonic". Arwel Hughes seems intent on blotting out major contrasts, stressing the "even tension" (as referred to by Ivashkin) in the work. For example, around 2 minutes in the first movement there is a passage in which the strings move emphatically down a scale against an accompanying, insistent figure in the brass. Typically, in the ECM recording the horns sound with Brucknerian grandeur whilst in the BIS recording they barely raise themselves above the symphonic tapestry. For the listener, the overall effect of Arwel Hughes' approach is not dissimilar to staring more than half an hour to a sea surface with an endless succession of wave superimposed upon wave. It demands very concentrated listening to keep hanging on to this. It might work but in my opinion two elements cause this brave effort to fail. First, the Cape Town orchestra is in my humble opinion not a major league player, lacking the polish and oomph to pull this off (listen how curiously underpowered and anemic they sound at the very beginning of the symphony). And, second, they are not at all helped by the rather indifferent acoustic perspective of the BIS recording, with bland sounding, recessed strings and disembodied winds. The ECM recording, on the other hand, offers just the right mix of weight and bloom to match Russell Davies' more grandiose conception. The BIS recording matches the Ninth with an alternative, as yet unrecorded version of the Concerto Grosso n° 1 (a version for flute, oboe, harpsichord, prepared piano and string orchestra, dating from 1988, instead of the original with two violins in the solo role). Despite the fact that it nicely complements Arwel Hughes' take on the Ninth (and, hence, might seem to strengthen the latter's case by stressing continuity with earlier elements in Schnittke's work), for me the BIS version of the Ninth does not really work and, for the time being, I remain wedded to the ECM recording. But as the re-tempoing experiment reveals, the latter is certainly not the end of the story and it is to be hoped that Chandos takes up the gauntlet and invites Valery Polyanski to proceed with his Chandos cycle." On the other hand... M. V. Sanderford | Danville, VA USA | 04/23/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "Regardless of the opinions rendered by our other two experts on the subject, let me just relate my experience with the work: I absolutely, flat-out, LOVE this symphony. More than any other work of Schnittke's, (and I have almost all of them in multiple recordings) this one hits home with me. I must have listened to this recording 100 times and every time I finish, I am profoundly moved and so thankful that (1) Schnittke got enough of it spelled out to produce this final product, and that (2) I heard THIS performance before the Davies one. I bought the Davies recording for comparison, and it's a disaster. Sorry. It doesn't work, at all, at any given moment. The third movement particularly is a dreadful slog at rehearsal tempos. Perhaps a Polyanski performance will blow this one away, but I'll be surprised if it does. This performance simple shakes me to the core - pretty impressive for one that is supposedly, flat, drab, and uninspired!!"

|

Track Listings (9) - Disc #1

Track Listings (9) - Disc #1