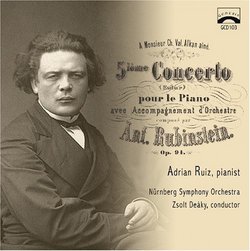

| All Artists: Anton Rubinstein, Zsolt Deaky, Nüremberg Symphony Orchestra, Adrian Ruiz Title: Rubinstein: Piano Concerto No. 5 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Genesis Records Release Date: 12/29/1993 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Instruments, Keyboard Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 009414810328, 902315001034 |

Search - Anton Rubinstein, Zsolt Deaky, Nüremberg Symphony Orchestra :: Rubinstein: Piano Concerto No. 5

| Anton Rubinstein, Zsolt Deaky, Nüremberg Symphony Orchestra Rubinstein: Piano Concerto No. 5 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD Reviews"I HAVE LIVED, LOVED, AND PLAYED." Melvyn M. Sobel | Freeport (Long Island), New York | 08/24/2001 (5 out of 5 stars) "Regarding the above quote, if the fifth piano concerto of the great Beethovenesque Russian bear, Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894), is any indication at all of his preference, he did far, far more of the latter than either of the former! However, since these ARE his words, and a good deal more succinct than his autobiography, who am I to speculate? Besides, it's a known fact that the man was near superhuman, anyway, a piano virtuoso reaching godhead proportions (during his lifetime). When he performed at the keyboard, women swooned and men fainted... or is it the other way around... or both? THAT'S the elemental power Rubinstein unleashed, obvious, still, over a hundred some odd years later. Even in the startlingly original and gloriously romantic first movement of his towering Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat, Op. 94--- the ne plus ultra of opening movements--- Rubinstein's twenty-one minute Allegro Moderato is a monumental affair, filled to overflowing with ripe tunes, exciting turns of phrase, ear-catching Slavic melancholy (heard as early on as the initial gorgeous chordal entry by the piano--- ah, sublime!), boundless pyro-technical amazements and ornamentations, seamless interweaving between soloist and orchestra, rampant poetic musings and a prolific sense of lyricism and composition. (Whew!) Easily, this movement epitomizes everything the Romantic era in music has come to be recognized for: its wealth of melody, strength of design, sensitivity and unparalled humanity--- all quite humbling. (As a matter of fact, I'm feeling a little faint here, myself.....) The Andante [11:02], almost funereal in its measured orchestral prelude, and quite a contrast to the thrilling running notes and orgasmic final chords that thunder shut the monolithic gates of the first movement, ushers in a piano solo of almost devotional poise and grace, continuing with very little orchestral support until nearly halfway through. Then, abruptly, the piano takes up the opening theme, quirkily marchlike, with rumblings in the bass--- and just as suddenly, quiets and becomes even more reverential as this unique movement comes to an end... before one even realizes that it has begun. It is an altogether metaphysical feat of musical magic. The final Allegro [16:01], of course, lets all hell break loose, especially after the "liturgy" of the Andante. Makes sense. Every trick Rubinstein has up his pianistic sleeves runs rampant and seemingly unchecked (which, naturally, it isn't) here in one of the most joyous, galant and freedom-loving romps imaginable. Up and down the keyboard we go, swirling, cascading, notes flourishing, chords hammering ascending and descending declarations--- the orchestra in hot pursuit--- melodies spouting, like musical geysers, here, there, everywhere, transformed or transmuted or harmonized in the most outrageously satisfying ways. It's a thrill ride from beginning to apocalyptic end! Needless to say, it takes a pianist of some moxie to tackle this behemoth of a concerto and, in 1971, Adrian Ruiz was certainly the right artist for the job. This Genesis CD release of that LP recording proves even more so today that Ruiz had the mettle, technique, panache, sensitivity and a complete Rubinstein simpatico with which to pull out every last stop and make this phenomenal concerto come alive. And he does, brilliantly! The Nuremburg Symphony Orchestra, under the able baton of maestro Zsolt Deaky, keeps marvelously apace, every detail, nuance and surprise intact. As well, Ruiz and Deaky are in total accord with Rubinstein's vision and completely responsive to each other. The sound has even more warmth and presence than the original LP, with a particularly bold piano image--- so critical for a concerto of this magnitude and scope. [Running time: 48:28]" A great performance: one with emotional depth and spirit. David A. Hollingsworth | Washington, DC USA | 12/29/1999 (5 out of 5 stars) "Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein (1829-1894) enjoyed great and longlasting success during his influential and important career. He was the instrumental force behind the establishment of the first institution for music training and education: the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music (with his brother Nikolai Rubinstein the founder of the Moscow Conservatory). Besides being influential, even a controversial figure in Russian musical circles, he was among the greatest pianist of the 19th Century. After his death, however, views concerning Rubinstein as a serious and important composer met with greater ambivalence than before. While there was a general recognition of Rubinstein's prolificity, music critics questioned and even attacked his art. M.D. Calvocoressi and Boris Asaf'yev deemed his art as un-imaginative and its idiom outdated and old-fashioned. It must be noted that Rubinstein was influential, especially upon Tchaikovsky when he embarked upon "Yevgeny Onegin" and his First Piano Concerto. It was not until the late 1970s when his music began to be re-examined and appreciated, though not in most repetoire. However, by the 1990s, the number of recordings of his works (especially for pianoforte) reached their highest peak: And that's a great thing. Rubinstein's Concerto for Piano and Orchestra no. 5 in E-Flat Major op. 94 (1874) is a noble and an orginal work, full of rich and warm melodies that Tchaikovsky owed thanks to when he composed his First Piano Concerto. The piano writing in Rubinstein's Fifth Concerto is demanding yet exciting but at the same time, poetic and charming. The First Movement is especially memorable and tuneful while the andante (Second Movement) is reflective with a degree of majesty. The Finale (allegro non troppo) is spirited and virtuosic. David Dubal, in his musical notes stated that "For today's listener, it will hardly matter if Rubinstein's concerto is either German or Russian enough. It makes good sound." With grace, I agree. Andrian Ruiz, the pianist in this recording, gave such an upmost authoritative and exhilariting performance that I wonder why his name rarely appear in the record world. His reading of the score is imaginative and telling and there's no doubt that his playing is among the best the recording world has ever witnessed. The conductor Zsolt Deaky had a firm command over the Nurnberg Symphony Orchestra which was responsive and enthusiastic. The recording sound is fresh and accurate despite the 1971 recording of the work. Recommended!" Forgotten Gem Benjamin R. Garrison | Lynnwood, WA United States | 06/10/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "This piano concerto does not deserve the obscure fate it was dealt. It is definitely underheard and underappreciated. If you're expecting clever Russian melodies here, you may be slightly disappointed, because Rubinstein is associated more with the traditional German school. This music is Schumanesque. With a touch of Liszt. There is a richness and depth of musicality and sophistication here that is neither bloated nor empty bombast. Just a lot of old fashioned goodness. Give this music a chance and you won't be disappointed. It sticks with you. The sound quality and performance are excellent. Buy it."

|

Track Listings (3) - Disc #1

Track Listings (3) - Disc #1