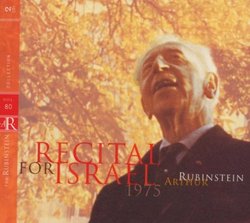

| All Artists: Rubinstein, Beethoven, Schumann, Debussy, Chop Title: Rubinstein Collection 80 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: RCA Original Release Date: 1/1/1975 Re-Release Date: 8/7/2001 Album Type: Original recording remastered Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Sonatas, Suites, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Romantic (c.1820-1910) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 090266308026 |

Search - Rubinstein, Beethoven, Schumann :: Rubinstein Collection 80

| Rubinstein, Beethoven, Schumann Rubinstein Collection 80 Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsShould Not Have Been Released on CD Hank Drake | Cleveland, OH United States | 09/30/2001 (2 out of 5 stars) "Arthur Rubinstein was notoriously picky about which recordings he authorized for release. He turned down most of RCA's requests to record his recitals. Of the twenty hours RCA taped at Rubinstein's marathon of Carnegie Hall recitals in 1960, he authorized the release of about 85 minutes of music (Volumes 39 & 42).The above is pointed out because this release, which stems from Rubinstein's only complete videotaped recital, was not authorized for release by the pianist. Toward the end of his performing career, the octogenarian pianist, who was suffering from macular degeneration and hearing loss, could have good days and bad days. This recital, taped in 1975 during Rubinstein's second-to-last season before the public, was definitely taped during one of his off days. The videotape at least has the saving grace of allowing the enthusiast to see, as well as hear, the pianist in action. But releasing the audio portion of that videotape does a disservice to the pianist's memory, who would surely have rejected its release. The Beethoven "Appassionata" Sonata is a case in point here. Rubinstein made three studio recordings of the work, the 1962 stereo version being his most successful attempt. As performed here, the piece is sectionalized, with heavy doses of outright pounding and very little structural control. There are many technical lapses and also a catastrophic memory lapse during the coda. Schumann's Fantasiestucke, Op. 12, was a great favorite of Rubinstein's. Again, he falls short of the mark here. Part of the problem here is that most of the time, the pianists simply plays too loudly. Rubinstein was never a fan of the feathery pianissimos that one would hear from a Gieseking or a Horowitz. But with his hearing failing him, the lack of any dynamics under mezzo-forte robs Schumann's music of much of its poetry. Only in the Debussy works does the pianist approach his best. Rubinstein was performing many of these pieces when they were hot off the press, and as often as not, being booed for playing such "abstract" modern music. The pianist knew these works so well he could probably play most of them in his sleep, and though he plays these works better in other recordings, these performances contain some of Rubinstein's hallmarks, the sensible tempos, innate structural sense without being pedantic, and natural phrasing. Rubinstein is generally recognized as the 20th Century's greatest Chopin interpreter, and with good reason. He led the shift away from the sentimental, feminine approach to Chopin, and toward interpretations which acknowledged Chopin's compositional genius. As with the Debussy, the Chopin is on a higher level than most of the recital. However, the repeated technical baubles in Rubinstein's signature A-flat Polonaise will send most fans scurrying listen to his many other versions--all of which are superior. The Mendelssohn Spinning Song recalls some of the grace of Rubinstein's best playing, and makes an effective encore.A note about the sound: Even when he was not at his best, Rubinstein's admirers would be ravished by the pianist's exceptionally beautiful sonority. Unfortunately, this recording was taken from the audio portion of the videotape, and sounds muddy and harsh."

|

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1