Rubbra's Monistic Vision

Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 12/11/2000

(4 out of 5 stars)

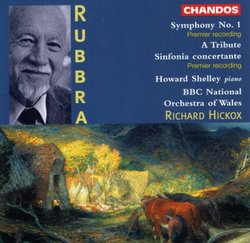

"Edmund Rubbra (1901-1986) studied with Cyril Scott at the Royal College of Music; he studied also and privately with Gustav Holst. Rubbra learned a great deal, although never his pupil, from Ralph Vaughan Williams. From RVW, Rubbra indeed absorbed his characteristic interest in modal polyphony and a mystical bent, which, however, he would pursue far more concertedly than Vaughan Williams, the confessed agnostic, ever did. Primarily a symphonist, Rubbra eventually wrote eleven examples of the genre. Together, they show a remarkably consistent development of the composer's austere style. The First Symphony (1936) - for decades more written about than performed - struck Wilfrid Mellers as exhibiting a "remorselessness" in its "free polyphony" and "an extreme nervous intensity that may properly be called contemporary" despite the work's archaizing atmosphere ("Edmund Rubbra and the Dominant Seventh"[1943]). Robert Layton has referred to the First's requirement for "enormous concentration" by the listener and suggests that the music rises in its level of procedural complexity to that of Bach's "Art of the Fugue" ("A Guide to the Symphony" [1993]). One must remember, in assessing such potentially intimidating remarks, that Rubbra's harmonies rarely step beyond the boundaries of those recognized by Brahms. One can say then his contemporaneity, unlike that of the Second Viennese School, does not stem from any abandonment of tonality. With qualification, the First Movement of the First Symphony begins with what sounds like a cross between Tudor counterpoint and Bachian fugal writing: A chorale of sorts in the brass against a great deal of busy support in the other choirs. The qualification is that Rubbra has written a movement as tempestuous, maybe more stormy, than that of Walton's First Symphony (roughly contemporaneous). Rubbra's music in fact outstrips Walton's in urgency and it makes the crisis of the opening Allegro of Vaughan Williams' Fourth (1934) seem tame by comparison. The Second Movement (of three) bears the title "Périgourdine." A chattering woodwind ensemble introduces the medieval French tune, innocent enough as it appears, but quickly complexifying itself contrapuntally into something uncanny and not a little bit threatening. The Third Movement (Lento) comprises a prelude and fugue (longer than the two preceeding movements combined) and forecasts the concluding movements both of the Third Symphony (1939) and the Seventh (1956), also fugal, or "monistic," as the musicologists say. Like Robert Simpson, his friend and (slightly younger compeer), Rubbra knew his Bach "by heart." The pedal-notes in the opening bars remind one of Sibelius, whom critics occasionally mention as an "influence" on Rubbra. The fugue occurs in slow tempi and emerges from the prelude so subtly (in a "Tallis Fantasia"-like string paragraph) that listeners might well miss its commencement. The stretto works up to a pitch of tempestuousness equivalent to that of the First Movement. The brass writing, especially the passages for solo trumpet, are hair-raising. One can only wonder why this remarkable symphony has remained obscure and unrecorded for six decades. The same puzzlement obtains where it concerns the Sinfonia Concertante for Piano and Orchestra (1934), dedicated to Holst, Rubbra's first substantial work after a series of chamber-music essays. It seems in many ways a rehearsal for the First Symphony, but tackles the additional formal complexity of reconciling the solo instrument with the orchestra. A drum-roll introduces the First Movement (Lento con Molto Rubato - Lento), whereupon the soloist describes a many-intervalled arpeggio ascending with calm strength from the lowest register of the keyboard. The string-choir gives support. We witness the same organic "unfoldment" or "evolution" as in the First Symphony (two years in the future): The same immediate polyphonic elaboration of the opening material, the atmosphere of crisis, the conflict of elements. The Second Movement (Allegro Vivace) takes the form of a Saltarello. The dance tune begins innocently enough but quickly assumes the character of something Dionysiac and menacing (anticipating the "Périgourdine" of the First Symphony). Howard Shelley's muscular pianism matches the controlled power of the music. Under Richard Hickox, the BBC Welsh National Orchestra plays with great clarity and precision. Hickox and the orchestra keep the equal lines of Rubbra's counterpoint separate and audible at all times. The noble Prelude and Fugue of the Sinfonia Concertante unfolds slowly, with impressive inevitability, through a precisely calculated graduation of dynamics. As a filler, Chandos gives us the brief (five minute) "Tribute" (1942) to Vaughan Williams, also basically a prelude and fugue. Only the "Tribute" has appeared before in recording, on an old Chandos LP led by Hans-Hubert Schönzeler."

After Vaughan Williams' 4th and Walton's 1st......

Rodney Gavin Bullock | Winchester, Hampshire Angleterre | 05/14/2001

(5 out of 5 stars)

"The first half of the 30s was an interesting time for English symphonic music. First Vaughan Williams abandoned his pastoral torpor with the grinding dissonances of his 4th symphony. Then William Walton produced his 1st (or most of it), though it sounds much gentler today than it did then. Finally, an unknown came along with his 1st - Edmund Rubbra. The first movement is terrifying - dissonant and bleak with a definite nordic atmosphere. Tapiola revisited. This is exciting music despite it being so densely scored. Temporary relief comes occasionally but the effect is like seeing the damage after a storm. Next comes a vigorous dance movement, a form which recurs in later symphonies. The last movement, of heavenly length, is beautiful and noble and it is here than we enter Rubbra's real musical world. That first movement was a one-off, never to be repeated. Some of the grimness is to be found in the 2nd symphony but after that it evaporated. This is a flawed work musically - the orchestration is invariably thick - but for me, at least, it does not matter. The Sinfonia Concertante is an earlier work. It is well worth hearing and ends with a rather wonderful fugue. The Tribute is a short work which was written for Vaughan Williams' 70th birthday. It is a charming little piece and very characteristic of the composer's style at the time of the 4th symphony. The performances are excellent, as is the recording. The notes are good too."

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1