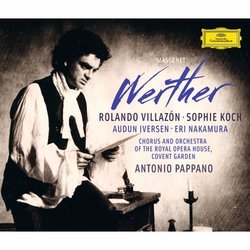

| All Artists: Rolando Villazón Title: Werther Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Deutsche Grammophon Release Date: 4/3/2012 Genre: Classical Style: Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 028947793403 |

Search - Rolando Villazón :: Werther

| Rolando Villazón Werther Genre: Classical

Werther is a work of Massenet's maturity, premiered in February 1892, just three months before his 50th birthday. By then he was a highly experienced and successful composer, with a sequence of acclaimed operas - Le Roi de... more » |

Larger Image |

CD Details

Synopsis

Product Description

Werther is a work of Massenet's maturity, premiered in February 1892, just three months before his 50th birthday. By then he was a highly experienced and successful composer, with a sequence of acclaimed operas - Le Roi de Lahore, Hérodiade, Manon, Le Cid, Esclarmonde - to his credit, several of which enjoyed international fame. But the origins of Werther go back quite some way. Paul Milliet, one of the three librettists responsible for the skilful operatic adaptation of Goethe's novel, described how the idea came up in February 1882 while he was travelling to Milan with Massenet and Georges Hartmann, the composer's publisher and occasional librettist, to attend the first Italian performances of Hérodiade at La Scala. At the end of a conversation about Goethe's novel and its operatic possibilities, it was agreed that Milliet should write a libretto for Massenet. He subsequently set to work, in consultation with Hartmann, spending several years on the task, while the composer kept busy with other projects. Massenet himself, in Mes Souvenirs (published in 1912, the year of his death), described how on a visit with Hartmann to Bayreuth in 1886 to hear Parsifal, the two then travelled to Wetzlar, the setting of Goethe's partly autobiographical story. After they had looked around the house where the original Charlotte had lived, Hartmann presented the composer with a translation of the book. In fact, Massenet, who meticulously dated his manuscripts, seems already to have begun writing Werther in the summer of 1885. He completed the vocal score on 14 March 1887, and was occupied with its orchestration until 2 July. Werther was initially turned down by Léon Carvalho, director of the Opéra-Comique, as being too dismal. Massenet then sat on the score for five years, awaiting more auspicious circumstances in which to unveil it. These finally presented themselves in the shape of a request for a new work from Wilhelm Jahn, director of the Vienna Court Opera, where Manon had notched up more than 100 performances. Composition of the score began earlier than these dates suggest, as soon as Massenet had some sort of text to work on. His regular practice with any libretto would be to memorize it, then to compose it in his head, usually while out walking, and then only when he was satisfied to put it down on paper. This is partly what gives his immaculate word-setting both its precision and its spontaneity. Few composers have ever set the French language with such a sensitive feeling for its natural inflections and expressive possibilities. Massenet's technical sophistication and flexibility are also demonstrated throughout the score by its fluidity of texture and structure. As a work conceived for the Opéra-Comique, Werther was heir to a long tradition that included spoken dialogue linking the musical numbers, as in Bizet's Carmen (1875). Massenet's own Manon (1884) retained the use of mélodrame - spoken text over an orchestral accompaniment - but Werther is through-composed, with no spoken text at all; and though it remains essentially a "number opera", with the characters moving into set pieces at emotional high-points, the joins between these "numbers" and the linking material are so well disguised that the listener is scarcely aware of any alteration in the level of discourse. Partly because of the masterly continuity of Werther, and partly because of its large-scale use of reminiscence motifs, critics right from the first tended to discern in it Wagnerian influences. But French music criticism at the time was obsessed with the question of "Wagnerisme", and all sorts of scores of the period were found to bear his influence. So it is with Werther, whose structural principles essentially represent a tightening-up of Massenet's own earlier procedures. In his use of reminiscence themes, he is developing a technique employed by French composers as far back as Méhul at the beginning of the 19th century. Werther went on to become one of the composer's most frequently staged works. Film director Benoît Jacquot's 2011 production at the Royal Opera House was conducted by the company's music director, Antonio Pappano, an interpreter of great flexibility and dramatic insight. As the Financial Times wrote, "the outstanding conducting of Antonio Pappano, working with a Royal Opera orchestra on top form, made sure that ... Massenet's opera blazed vividly into life." It was undoubtedly Pappano's unique artistry that laid the bedrock for a highly successful musical performance. Rolando Villazón sang the title part, one of opera's great outsider figures and one of the Mexican tenor's signature roles, which he first assumed in Nice in 2006 and later at the Vienna Opera in 2008 as well as in Paris; the opera also marked his directorial debut in Lyon in 2011. Of Villazón's return to Covent Garden for this performance, the Guardian critic wrote: "His artistry is as astonishing as ever, fusing sound, sense and gesture in an uncompromising quest for veracity." Alongside him the French mezzo Sophie Koch sang the tragically conflicted Charlotte - for her, too, a kind of signature role in which she has been acclaimed in Vienna, Madrid and Paris as well as London. The Japanese Eri Nakamura personified Charlotte's spirited younger sister Sophie, the Norwegian baritone Audun Iversen her unloved husband Albert, and the distinguished French baritone Alain Vernhes her solidly bourgeois father, the Bailiff. George Hall

Similar CDs

| Renée Fleming Poemes Genre: Classical Label: Decca Records | |

Track Listings (24) - Disc #1

Track Listings (24) - Disc #1