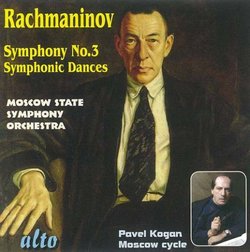

| All Artists: Sergey Rachmaninov, Pavel Kogan, Moscow State Symphony Orchestra Title: Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 3; Symphonic Dances Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Musical Concepts Original Release Date: 1/1/2008 Re-Release Date: 10/14/2008 Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 894640001301 |

Search - Sergey Rachmaninov, Pavel Kogan, Moscow State Symphony Orchestra :: Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 3; Symphonic Dances

| Sergey Rachmaninov, Pavel Kogan, Moscow State Symphony Orchestra Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 3; Symphonic Dances Genres: Dance & Electronic, Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsIn the ranks of Golovanov and Svetlanov Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 07/01/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "Sergey Rachmaninoff (1873 - 1943) has something in common with Hector Berlioz and William Walton - a restricted oeuvre that is necessarily much duplicated in the available discography. Of course, every pianist worth his digits wants to set his seal on the Second and Third Concertos and the Paganini Rhapsody, and many integral sets of the four concertos and the rhapsody exist. Conductors have regularly advocated Rachmaninoff as a purely orchestral composer. In the category of orchestral music there are, first of all, the three symphonies so-called, the choral symphony "The Bells," the Symphonic Dances (a symphony in all but name), and the tone poem "The Isle of the Dead." The Second Symphony (1908) has been a popular favorite since its debut although for many decades conductors played it with cuts, while the Third Symphony (1938) had early champions in Eugene Ormandy and Leopold Stokowski. The story of the First Symphony (1898) is well known: How a botched first performance under Alexander Glazunov put the score in a bad light, how Rachmaninoff, wounded, withdrew it, and how after his death Russian musicology restored the work, which is many ways the composer's most vivid and tightly controlled foray into strict symphonic form. Yevgeny Svetlanov, André Previn, Edo de Waart, David Zinman, Valery Gergiev, Yuri Temirkanov, and Mikhail Pletnev, among others, produced integral recordings of Rachmaninoff's symphonic works in the stereo and digital eras. New sets of these works face stiff competition and must rise considerably above any average in order to be worthy of notice.

Pavel Kogan's early-1990s traversal of Rachmaninoff's orchestral oeuvre with the Moscow State Symphony, only just now coming into the catalogue on the Alto label, moves to the top of the list in all three Rachmaninoff symphonies. As is typical, Kogan's program couples the Third Symphony (begun in 1936 and premiered in 1938) with the late Symphonic Dances (premiered in 1942 shortly after its completion in score). Of the three Symphonies so-named, the Third requires the shortest performance-time, clocking in at around thirty-five minutes; the Symphonic Dances has almost the same duration. One mark of a superb Rachmaninoff symphonic cycle is the conductor's ability to approach the scores on their own terms as individual works. Of course, an unmistakable "Rachmaninoff sound" informs all four items, but while remaining true to himself Rachmaninoff's style changed in subtle ways over the decades. Thus the First Symphony tends to dispose the instruments in choirs, maintaining a distinction between the strings, woodwinds, and brass; the Second Symphony achieves a more blended, "Romantic" sound (in common with the tone poem "The Isle of the Dead"). Both the Third Symphony (A-Minor) and the Symphonic Dances find the composer drawing on the resources of a large orchestra to create diaphanous, chamber-music-like textures in addition to luxurious tutti gestures when needed. The Third Symphony uses a celesta, often combined with the two harps, to produce glittering highlights in all three movements. The Symphonic Dances uses an orchestral piano in all three movements and, in the First Movement, a solo saxophone, which dominates the middle section of the movement. Kogan understands that Rachmaninoff was both a melodic composer and a rhythmic composer - and that, as the latter, he could at times rival Stravinsky in his ingenuity. Kogan also understands that, in the Third Symphony and the Symphonic Dances, Rachmaninoff is dispensing with the pervasive "Romantic" gestures that characterize his most famous scores, the Second and Third Concertos and the Second Symphony. The opening of the Third Symphony is a case in point: A brief slow introduction leads to a sudden outburst, all brass and drums, a Petrushka-like "call to attention," which is then followed by an extraordinary profusion of short motifs in the woodwinds and strings, all of which Rachmaninoff will exploit, not only in the remainder of the movement, but across the whole symphony. Next, as a kind of "second subject," comes the familiar, prolonged "big melody," given to the cellos. The development is complex: it breaks down the "big tune" and combines it with motifs from the introductory paragraph. Kogan keeps the "big picture" together, so that the incidents all have their proper context. In an old BBC Music Guide, Patrick Piggott characterized the Rachmaninoff's Third as being "one of his best works" and as being "of considerable originality." Kogan manages the whole with something approaching perfection. The Second and Third Movements are equally articulate and equally polished in Kogan's performance. In verve, Kogan's interpretation resembles older performances by Nicolai Golovanov and Yevgeny Svetlanov. In three movements like the Third Symphony, the Symphonic Dances take even further the Third Symphony's modernism, its innovative scoring and leanness of texture, and its rhythmic audacity. The second subject of the First Movement is a test for the interpretation. The theme is given to the alto saxophone, and the timbre is suggestive of jazz, or even of the Blues; but the melodic outline is reminiscent of the composer's "Solemn Vespers" and, more generally, of Orthodox chant. As in the case of Svetlanov, Kogan gives a deeply Slavic reading of Rachmaninoff's score. " |