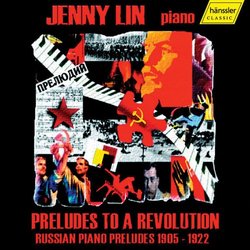

| All Artists: Anatol Lyadov, Boris Pasternak, Serge Bortkiewicz, Alexey Vladimirovich Stanchinsky, Arthur Vincent Lourie, Anatol Alexandrov, Alexander Scriabin, Nicolas Obukhov, Ivan Vishnegradsky, Samuel Feinberg, Nikolai Roslavets, Reinhold Gliere, Jenny Lin Title: Preludes to a Revolution Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Hanssler Classics Original Release Date: 1/1/2005 Re-Release Date: 6/14/2005 Genres: Special Interest, Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 040888848028, 4010276014973 |

Search - Anatol Lyadov, Boris Pasternak, Serge Bortkiewicz :: Preludes to a Revolution

| Anatol Lyadov, Boris Pasternak, Serge Bortkiewicz Preludes to a Revolution Genres: Special Interest, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs

|

CD ReviewsA fascinating idea.... Sue Leigh Waugh | WA | 10/21/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "Now here's an interesting study! 41 little preludes arranged in chronological order from Liadov's Opus 57:1 and Gliere's Opus 26:1 (both written in 1906) through to Nikolai Roslavets's Five Preludes of 1919-22. In between we have seven by Alexei Stanchinsky written between 1907 and 1908 and five Fragile Preludes by Arthur Lourie, his Op.1, written from 1908 to 1910. Then there's a break in continuity. We pick up with Anatoli Alexandrov's four Preludes, Op. 10 from 1915. So far the romantic has given way gradually to the uneasy, but the four-year break (and, no doubt the change of composers) leads us abruptly into the chromatic-a tendency that Scriabin's Op. 74 does naught to mitigate. I presume the placement of Alexandrov here rather than after the Scriabin {1914) and Nikolai Obouhov {1914-15) is to make the point gently at first. Obouhov's seven pieces are also called Prayers. Less harmonically individual than Scriabin's, they have an exploratory quality that is evocative of the period. He has a fondness for parallel harmonies that head out into the great unknown. Ivan Wyschnegradsky's two of Op. 2 of 1916 make similar moves with less finesse. Samuel Feinberg's four, Op. 8 {1918-19?) are grounded in searching but repetitive harmonies while rhythmically they are more straightforward and aggressive. Finally comes Roslavets, back in the Scriabin camp at this period. It is a fascinating idea to unify a program this way. Lin plays with sensitivity and emotional depth. Among the felicities in the liner notes is a time-line of Russia from 1900 to 1930. But that's icing on the cake. There's enough unfamiliar Russian music here to educate us for some time. - D. Moore, American Record Guide " Classics Today 10/10 - Highest Rating Sue Leigh Waugh | WA | 10/21/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "Pianist Jenny Lin's first (and hopefully not last) solo outing for Hänssler Classic brings us a rich gallery of Russian piano preludes dating from the decade before the 1917 Revolution and continuing through 1922. No doubt some composers' names here are more familiar than others, and not all of them are bonafide original creative voices--yet all of the pieces are interesting. The tonal ambiguity and mystic aura typifying late Scriabin (such as in his Op. 74 Preludes) also are evident in the Alexandrov Op. 10 Preludes, although No. 2 seems to morph Liszt's Valse Oubliée No. 1 onto Ravel. Samuel Feinberg's Op. 8 takes late Scriabin into more garish, polytextural territory à la Godowsky. By contrast, Nikolai Obouhov's starker keyboard deployment and quirky dynamic shifts sometimes foreshadow Messiaen's bell-like block chords and bird-like decorations. A delicate and evocative set of Preludes by the teenaged Arthur Vincent Lourié bears no hint of the Futurist iconoclast to come. And in Nikolai Roslavetz's Five Preludes, desolation and tender lyricism poignantly cohabit. As usual, Lin's talent for creating enterprising programs is matched by intelligent musicianship, a technique that can handle anything, and a big, generous tone. She gives the charming Liadov Prelude a stronger sense of line and lilt than Olga Kern's less-shapely rendition, and she matches the slashing intensity of Piers Lane's splendid Scriabin Op. 74 group with just a little more room for the bass lines to heave their angst. The excellent annotations and engineering further seal my highest recommendation. --Jed Distler " Revolution for what? scarecrow | Chicago, Illinois United States | 03/06/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "What any of this music has to to do with the Bolshevik Revolution, or the previous one of 1905,or the Famine of 1921-22 given the inflammatory cover here is anyones guess. Perhaps the proximity alone in chronologic years gives a clue, but judging from the fairly cloistered conservative content of the music here,more for the Czar and the Russian middle classes the boyars and aristocracy,there's not much "revolution", where are all the revolutionary tunes portrayed??Even with the nice elaborate Time-Line given surrounding this time 1900-1930.I thinks literature better expressed these times,more graphically as the ravages in Andrei Platonov's novels,or the more innovative (technically) of Vladimir Khlebnikov. There was tunes to render in solidarity with the Bolsheviks,perhaps that was not desired! or The Internationale? This is music of What was! of post-revolutionary Russian, as Liadov's floating Chopin-esque D-Flat Prelude. This bunch was quite lyrical however,it was the language of this time,escape into a melody,a melos, quite evocative,odious, more music for the parlor, the afternoon tea round the samovar, than the peasants trudging their oxen in the manured mud, or the odious blasts of sulfur choking to death theteenage children that worked the Czar's steel mills. The more progressive "lights" here happen to be those of innovation of Wyschnegradsky who had enough and eventually emigrated to France to explore his new tunings of the pianos pieces, quite impressive. Here we have the old, and Nikolai Roslavets perhaps the first atonal composer from this period, with his impressive chromatic textural and lyrical preludes are for me the substance of musical progress for this time.His Preludes are quite rhythmically free. All else is escapes as Scriabin into further dimensions of the spiritual to devoid/negate the self the time, not be a part of it. Lacan said we really do not want to know reality, so we attach to it through the imagination, through "other" parts of our psychologies,as these composers. We do this with "prayers" as composer Obouhov,"prayers" for restoration I suspect. Well industrialization and worse befell Mother Russia surrounded by the West, who would not allow the Bolshevik experiment to take root, and culture to had to find other means, perhaps through circumvention of reality as Shostakovich had later revealed to us, only through subterfuge can the "revolution" have commentary, or none at all. The playing is superb, clean bright, and precise."

|

Track Listings (41) - Disc #1

Track Listings (41) - Disc #1