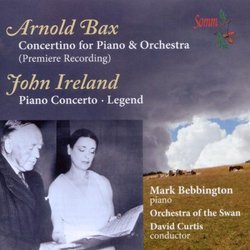

| All Artists: Bax, Ireland, Bebbington Title: Piano Concertos Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Somm Recordings Original Release Date: 1/1/2010 Re-Release Date: 4/13/2010 Genre: Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 748871324220 |

Search - Bax, Ireland, Bebbington :: Piano Concertos

CD DetailsSimilar CDs

|

CD ReviewsBax Broods Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 05/09/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "In 1970 Sir Arnold Bax (1883 - 1953) was a name that one encountered in books about British music, but his extensive oeuvre remained mostly unrecorded. In 2010 virtually every note that Bax penned in his steadily creative life has found its way into the available discography. There are indeed no less than three integral recordings of his seven symphonies. In such rich circumstances, a hitherto unknown Bax score is bound to generate interest, not least when it rivals in scale other major works by the same composer. Bax wrote his Concertino for Piano and Orchestra in 1939 for pianist Harriett Cohen, with whom Bax had maintained a decades-long liaison, divorcing his wife for Cohen's sake but never marrying her. Cohen played the role not only of Bax's lover (although by 1939 the Eros had gone out of the affair) but also of his major keyboard advocate, accepting the stewardship of the Symphonic Variations (1916), the Winter Legends (a symphony concertante, 1929), the Saga Fragment (1932), and later on of his Concertante for Piano (Left Hand) and Orchestra (1949), among others. Cohen also monopolized performance of these works, which made her association with them ambiguous, as far as knowledge of Bax's work went. Others might have served Bax had Cohen's proprietary insistence not prevented them from doing so.

The Concertino (whose modest designation belies its scope) belongs to Bax's late phase, being exactly contemporary with the Seventh Symphony (1939) and sharing its esthetic with the tone poem A Legend (1944). But by the outbreak of the war, Bax's creative energy was tapering off. Bax never completed the orchestration of the Concertino, which, unperformed, disappeared seemingly into oblivion. Such is the indefatigable devotion of Bax scholarship, however, that several supposedly lost scores have come to light - including now the Concertino itself; and such is the interest of Bax's posthumous audience in his work that bringing the score to performance has been possible. Undertaking the formidable task, Bax scholar Graham Parlett, working from indications in the manuscript, was able plausibly to realize Bax's intentions concerning the orchestral part. Parlett brought to the task not only his detailed knowledge of Bax's style, but also his previous experience in orchestrating two of Bax's compositions. Parlett orchestrated an interlude, On the Sea Shore, from Bax's early, never completed opera Deirdre (1908) some twenty years ago and later he did the same for the two-piano piece Red Autumn (1912). The late Vernon Handley recorded both items for Chandos. The Concertino would pose a much greater challenge. Parlett's own program notes for the Concertino's premiere state that "Bax left only a few indications of the intended orchestration (`str con sord' [muted strings] and `fag' [bassoons] appear at the opening, for example), but it is clear from the layout of the music that a fairly large orchestra would have been required." In places, Bax having indicated only chords, Parlett had to invent Bax-like figurations to overcome what would otherwise have made an "intolerably static impression." The result abundantly justifies the effort. The Concertino is an altogether more serious and essentially "Baxian" score than the Cello Concerto (1932), the Violin Concerto (1938), or the subsequent Concertante. Parlett in his notes refers to the work's "dark" quality. The First Movement's opening, scalar descending theme in the solo part manages to evoke all at once both the familiar Baxian otherworldly mood and a sense of powerful this-worldly anxiety. The keyboard textures in Symphonic Variations and Winter Legends are thick, with great handfuls of notes; but in the Concertino, the solo part is generally less massive than in the earlier scores. A second subject, ballad-like in character (parallels for which in the Bax oeuvre will occur to all initiated listeners), changes the mood somewhat, from anxiously contemplative to grimly determined. There is a fanfare for solo trumpet. The development involves motifs derived from all these separate elements. The Second Movement begins as a nocturne, mainly with string accompaniment; this becomes a brooding funeral march at the midpoint of the movement, which then, by modulation, becomes the subject of a Baxian "visionary moment" (so to speak). The concluding bars of the middle panel of the triptych involve a duet between the keyboardist and the first horn. Here Parlett's Baxian sensitivity has really paid off. In the Third Movement, Bax lightens the atmosphere considerably, with a series of Ballabile motifs and some aggressive gestures in his Iroquois war-party rhythm. Not quite as "big" as Winter Legends, the Concertino is nevertheless "bigger" by far than the Concertante. David Curtis leads the Orchestra of the Swan, an orchestral ensemble larger than the typical chamber orchestra but smaller than a big-time philharmonic. Mark Bebbington is the soloist, not only for the Concertino, but also for the two John Ireland items that balance out the program - the Piano Concerto (1930) and the Legend (1934). Ireland's Concerto is unobjectionable and full of charm without being profound. The Legend, on the other hand, is a haunting score and an apt companion to the Bax Concertino. Parlett deserves the gratitude of all Baxians for rescuing this important work from oblivion. " |