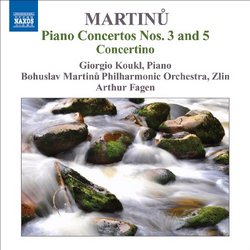

| All Artists: Koukl, Bohuslav Martinu Po, Fagen Title: Piano Concertos Nos 3 & 5 Concertino Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Original Release Date: 1/1/2010 Re-Release Date: 1/26/2010 Genre: Classical Style: Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 747313220670 |

Search - Koukl, Bohuslav Martinu Po, Fagen :: Piano Concertos Nos 3 & 5 Concertino

CD Details |

CD ReviewsGood enough. Marvellous music in second-best performances Bert vanC Bailey | Ottawa, Canada | 05/09/2010 (3 out of 5 stars) "Bohuslav Martinü composed at least fifteen works for piano and orchestra by my count, and all of them deserve more attention. Nor has his fame lived up to the high quality of his large output in all musical areas. I would run to any live Martinü performance, yet can count those I've attended on one hand ...and have fingers to spare. Let's hope this new series helps change that. His music's rhythmic convolutions and frequent, often unexpected, changes in tempo can challenge first-time listeners. Interpreters who avoid sounding drab and can draw the real goods out of this rather quirky music have a firm grasp of this. An unusual, rather eerie beauty also often emerges from Martinü's slow movements, and, given those wayward tempos, from slow passages within the faster ones. His best interpreters, again, deliver this with subtle texturing and a strong dynamic sense. In short, it's easy for artists to get his music wrong, and to noodle through what abler hands can turn into delightful, sometimes transfixing music. This CD will be appraised through the prism of the closing Allegro of the 1938 Concertino - only one of its nine movements, but a microcosm of the recording. The orchestra under Fagen handles several surging passages (e.g. 4:30-5:01) very capably, along with various Martinüesque changes in tempo and rhythm (such as at 4:05-4:10), although some orchestral dragging and a lack of synchrony also occasionally show (5:02-5:07). The movement is launched forcefully, but the ensemble seems to lose focus and come under some strain around 1:17 to 1:20. The BMPO supports Koukl with nicely-shaped flourishes when he takes the spotlight (1:47-3:28), but the winds sound only partly engaged - particularly an oboe's perfunctorily-delivered refrain (3:29-3:32) in a musical plateau between two rousing passages. The movement is well-spurred into a surging gallop from 4:56 to 5:12, yet some rhythmic tripping occurs between the timpani, whose beat redoubles at 5:13, and the other players - who should all be charging headlong toward the climax. The strings catch up to the beat, but the culminating trumpet fanfare at 5:19 is under-profiled and the orchestra does not deliver an effective culmination that outdoes the earlier, false one (at 1:33). What follows this peak seems almost an afterthought from the near-reticent orchestra. Granted, more conventional composers would arguably decide either to end straight after the climax or to add a few measures and delay the end. But this is Martinü, and from 5:32 to 6:00 the muted horns, pizzicato strings and various other instrumentalists sound almost laconic; after that, the proceedings rise to a tutti but rather unceremonious end. By contrast, the performance by Jiri Belohlavek with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Emil Leichner at the piano, of the Martinü: Piano Concertos is another thing entirely. The Czechs under Belohlavek summon build-ups effectively in this movement of the Concertino, and they also create subtle, contemplative passages; the music's rhythmic core is also far better in hand through sharper execution. Better considered as well is the sound spacing to suit the music's needs - whereas the Naxos sound seems uncharacteristically flat. The sound is better adjusted in the Supraphon both in shifting instrumental groups for emphasis into the fore or background for emphasis, and in volume dynamics according to the drama. All of these result in a performance that is full of conviction: more strident and razor-sharp where needed, and better-nuanced where sensitivity is required. Belohlavek coaxes colour and ornamentation from the orchestra both to accent and add contour to the soloist's part, as against acting in alternation with the pianist. Leichner ends up not as in the fore as Koukl: his part is more closely integrated with the orchestra (the same holds for the timpanist, incidentally, who also stands out much less). The Czech Phil's tighter ensemble delivers slow passages of great refinement while also managing robust, hair-raising fortissimo execution when that's called for. This last is done with jazzy flair on the trumpets' climactic entry (5:10 here): the players are all but seen to rise and blast out their brief part with dizzy exuberance. Closer attention to the shape of what remains after this peak also brings out some more tightly-wound, eventful music -- just listen to those lovely, long pizzicato lines of cellos and double basses shaping the closing passages, which leave no sense of disappointment when the end arrives. At best, unlike Supraphon, Naxos provided insufficient rehearsal time. Giorgio Koukl does perform admirably, although Fagen's BMPO does not quite rise to that standard. The often-read reference to Naxos's low pricing must be invoked, since, to be clear, this is no amateur effort nor artistic disaster: there remains plenty to enjoy here, and in the rest of the recording. This CD is certainly recommended: Martinü is, very simply, *that* engaging. At this price it's a must for any music-lover -- especially if Martinü's new to you. But if the Supraphon with Leichner/Belohlavek is within your grasp, that's the one you want." Little Known Concertos of Martinu D. A Wend | Buffalo Grove, IL USA | 04/09/2010 (5 out of 5 stars) "Bohuslav Martinu was born in the Czech Republic in 1890 and moved to Paris in the 1920s to study music with Albert Roussel. He lived in the United States from 1940 fleeing the war in Europe. It was in the United States that his symphonies were written and the Third Piano Concerto which was on a request from pianist Rudolph Firkusny. The concerto was written during 1947 and premiered by the Dallas Symphony in 1949. The work is neo-classical and begins with a long orchestral introduction prior to the entrance of the soloist. For anyone who knows the music of Martinu, his thematic development will be familiar along with his characteristic "twinge."

The concerto is an engaging work with spectacular interplay between soloist and orchestra in the first movement, a Brahmsian andante that contains some brilliant music beautifully blending orchestra and soloist. The finale begins with a brief phrase by the orchestra; the soloist enters with a lively melody, which is developed to a climax and is followed by more reflective and mysterious music, gradually becoming livelier again. A brilliant cadenza takes us back to the beginning melody played by the orchestra followed by a rousing interplay between soloist and orchestra concluding on an optimistic chord. The Fifth Concerto was written in 1957 by which time Martinu had moved to Switzerland. An ominous chord from the brass opens the concerto, which bears the designation Fantasia concertante. The opening movement has the composer's characteristic seven-note theme worked into an effective interplay between the soloist and orchestra. The second movement begins with long peaceful chords played by the orchestra. The piano joins and the peaceful mood continues and gradually becomes more agitated, moving into a passage of shimmering trills. The finale begins on an exuberant note developing to a lyrical middle section. The Concertino for Piano and Orchestra dates from 1938. It is a lively work characterized in the first movement with jazz-like syncopated chords. The middle movement is lyrical and is followed by an exuberant finale. The Bohuslav Martinu Philharmonic Orchestra under Arthur Fagen performs beautifully and more than ably supports the soloist Giorgio Koukl, who performs the demanding concertos with enthusiasm. A highly recommended disc. " |