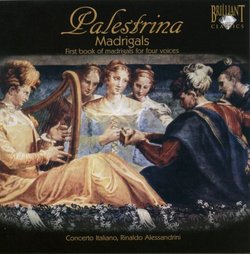

| All Artists: Concerto Italiano, Andrea Damiani Title: Palestrina, Il Primo Libro de Madrigali Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Aphrodisio Recording Original Release Date: 1/1/2008 Re-Release Date: 12/11/2007 Genres: Special Interest, Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 842977033649 |

Search - Concerto Italiano, Andrea Damiani :: Palestrina, Il Primo Libro de Madrigali

| Concerto Italiano, Andrea Damiani Palestrina, Il Primo Libro de Madrigali Genres: Special Interest, Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsWhat Makes One-on-a-part Polyphony Superior? Giordano Bruno | Wherever I am, I am. | 11/08/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "We can make a comparison to answer that question, but you'll have to buy this very fine CD to follow what I'm saying. (Actually, you can make the same comparison with two CDs of music by Josquin just as well, one by the Tallis Scholars and one by the Clerks' Group or the Orlando Consort.) I've been on a Palestrina jag for the last few days, listening to the 5 CD box of Palestrina masses performed by Pro Cantione Antiqua, singing two on a part. Their performance is excellent by choral standards, but....

Listen to the four voices of Concerto Italiano singing the four lines of polyphony in these madrigals. Notice that you can easily hear the individual timbre of each voice, and thus that you can follow the interweaving of the four voices independently. If your listening skills are honed, you can listen to all four voices simultaneously yet keep them distinct from each other. You can't do that on a choral recording. Notice also that each voice has its own affect, its own expressive quality. You can't hear that in a choral performance. Listen to the articulations and enunciation - the consonants and vowels. Notice how crisp and precise they are in each line, and how that kind of articulation colors the rhythm of the music. Notice how potent it becomes then when all four voices articulate a word together. You can't get that kind of clarity of rhetoric even with two on a part. Listen to the cadences (finishes of phrases), where the four voices of different timbre suddenly blend into perfectly tuned chords. You can't hear that contrasting of dissonance and consonance with the muffled "compromise" tuning of a multi-voiced chorus. Listen to the independence of the four voices, in rhythm, dynamics, and even phrasing, so that you NEVER feel that the music is being conducted from a podium. You can't get that kind of flexibility from a chorus, even a two-on-a-part chorus. Giovanni Luigi di Palestrina (1525-1596) was appointed by Pope Julius III to the Papal Choir in Rome in January of 1555, the best job a musician could aspire to in the mid 16th C. He was dismissed from the choir just six months later by a new Pope, Paul IV, because of his status as a married man. His First Book of Madrigals, settings of love poems by Petrarch and others, may have been published the same year. It's odd to think of Palestrina, the later darling of the Counterreformation Catholic intelligensia, as a victim of fanatical commitment to celibacy. But Palestrina, even as a young man, was an Apollonian rather than Dionysian composer, more committed to perfecting his mastery of a conservative style than to emotive novelty. These madrigals are emotive, more so than Palestrina's multitudinous sacred compositions, and very suavely beautiful, but the basic harmonic vocabulary is the same as that of his masses and motets. Concerto Italiano is unsurpassed at this repertoire. The only thing I regret, listening to this CD, is that they haven't recorded at least a few of Palestrina's glorious masses.... one on a part, of course." |

Track Listings (29) - Disc #1

Track Listings (29) - Disc #1