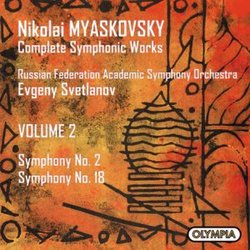

| All Artists: Myaskovsky, Svetlanov, Russian Fed Academic So Title: Myaskovsky: Complete Symphonic Works, Volume 2: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 18 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Olympia Original Release Date: 1/1/2002 Re-Release Date: 5/28/2002 Genre: Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 5015524407322, 515524407322 |

Search - Myaskovsky, Svetlanov, Russian Fed Academic So :: Myaskovsky: Complete Symphonic Works, Volume 2: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 18

| Myaskovsky, Svetlanov, Russian Fed Academic So Myaskovsky: Complete Symphonic Works, Volume 2: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 18 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsAn Important Series of an Important yet underrated Soviet II David A. Hollingsworth | Washington, DC USA | 11/27/2002 (5 out of 5 stars) "What makes Myaskovsky worthy of admiration today was his capacity and choice in enhancing musical art in the Soviet Regime under Stalin from the mere conformity towards Socialist Realism and gave it more authenticity and credibility. He was not a bold musical statesman like Shostakovich and Prokofiev. But he was relentless, his own man, and in many ways autobiographical and personal as Tchaikovsky was generations before and like his near contemporaries such as Bax and Martinu. His music is somewhat of a journey from searching for his personal voice to actually finding it while making it accessible to listeners in Russia and beyond. Listening to his music, you can be assured of depth and substance behind his compositions permeating with an euphonious sense of genuinity and dignity. The Second Symphony (1910) serves as an effective foretaste to the Scriabin-ladened Third Symphony (1913). In terms of fiery temperament, it relates to the early piano sonatas (namely nos. 1-4). The influence of Scriabin is notable especially in the first movement. But listen further and you'll sense something Tchaikovskian and Mahlerian in its manic, intense expressionism. It's particularly daring & powerful, with despairing climaxes & intensity. The slow movement is a bit more compelling I found. It is among his most deeply felt and memorable of all the slow movements of his large-scaled works. What comes to mind is perhaps an accidental relation with the slow movements of Lyatoshynsky's First and Third Symphonies in its mystic themes, pseudo Scriabinian & Rachmaninovian emotionalism & beauty. The movement is remarkably appealing & poetic. The last movement returns to where the first movement left off, with the same level of intensity & pessimism, with the sense of optimism trying to assert itself, only to be overcome by the anguish nature of this impressive, promising student work (completed while Myaskovsky attended the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music). The Eighteenth Symphony (1937) is altogether a simpler, albeit a less adventurous work (even less dramatic and emotionally profound than the Seventeenth of 1936-1937). It was dedicated to the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution and the height of the Stalin purges and the enforcement of Socialist Realist policies at that time compelled everyone to go on a safe road and not take risks (hence, the Finale of Shostakovich Fifth Symphony written the same year). The Symphony instead is songlike throughout. It has a strong Slavic feeling to it and the ideas are of exceptional clarity. The discursive first movement begins with a strong motoric theme that recurs throughout (and somewhat in a manner of Rimsky-Korsakov) while the following secondary, recurring theme (@ 1'12''-ff) is dancelike in character (like slowly riding in a horse-drawn wagon passing through a Russian pastoral landscape). The second movement is highly serene and meditative and a foretaste to the 23rd Symphony in its coloristic facets & qualities throughout. The finale is likewise dancelike, strongly Slavic in character and temperament, but with gusto and exuberance. According to Alexei Ikonnikov, the composer's chief biographer, the work was so appealing that a farmer, Sergey Ivanovich Korsakov, wasted no time sending a letter of praise to the composer via a fellow Professor A.A. Alschvang.The performances of Svetlanov and the State Symphony Orchestra of Russia are committed and authoritative, with a sense of flair especially in the slow movements. The Second Symphony is bestowed with two other very good recordings currently available: Gennady Rozhdestvensky with the USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony (Russian Revelation) and Gottfried Rabl with the Vienna Radio Symphony (Orfeo). Rozhdestvensky is no doubt to most compelling, bringing out the manic depression and pessimism behind the work most naturally. His approach of the slow movement is particularly spillbinding. Rabl, not as sonorous as Rozhdestvensky and Svetlanov, has the advantage of pure dramatic sweep and edge that keep the music from sounding longwinded (and the Orfeo is more superior). Svetlanov's rendition of the work is not as ideal as Rozhdestvensky's, but its strong Russian ardency is a good enough incentive for acquisition. And since the Second Symphony is coupled with the Eighteenth (in its only digital recording, though recorded by Melodiya roughly five decades ago featuring Gauk and the Moscow Radio Symphony not widely available) the incentive for acquisition becomes even greater. Therefore, I would suggest purchasing these three recordings of the Second Symphony. Meanwhile, eagerly look forward to Volume III, with Myaskovsky's Third & Thirteenth Symphonies. The Thirteenth is a qualified masterpiece that went a step further from the Twelfth Symphony in the inner-conflictive turn-around from the overtly personal to the idiomatic musical representative of the Soviets (and deceptively & defiantly beyond the Soviets). --->A heartfelt tribute is due to Yevgeny Fedorovich Svetlanov, who passed away on May 3rd. He was, arguably, the chief representative of Russian music, exposing us to obscure works of Russian and Non-Russian composers (like Glazunov, Lyapunov, Shaporin, and Alfven for instance) that, perhaps, would not otherwise be exposed. His career as conductor, pianist, and composer was long and influential, and he was truly enterprising throughout, while never afraid to let himself go. Although it's regrettable that he could have done much more to revitalize Russian opera, he will continue to be honored as among the conductors (not so many, by the way) who not only made a career in promoting obscured works, but also giving meaning behind a particular piece, famous and not so famous. Svetlanov remained faithful and genuine in his approach to a given music and the affinity he had towards a piece was so strong that when performing Tchaikovsky, Svetlanov became Tchaikovsky, when playing Glazunov, Svetlanov became Glazunov, and so forth. He is a jewel of Russian musical culture, and therefore, his devotions will not be strewn in memory especially of those who benefited from all that he gave us for over five decades. I dare hope that recording companies would take it upon themselves to revitalize his recordings, especially of his performances of Medtner's works for pianoforte, since less than five percent are available so far. Until next time."

|

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1