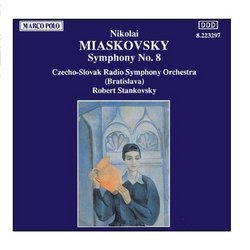

| All Artists: Robert Stankovsky, Nikolay Myaskovsky, Czecho-Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra (Bratislava) Title: MYASKOVSKY: Symphony No. 8 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Marco-Polo Release Date: 8/4/2009 Genre: Classical Styles: Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 730099329729 |

Search - Robert Stankovsky, Nikolay Myaskovsky, Czecho-Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra (Bratislava) :: MYASKOVSKY: Symphony No. 8

| Robert Stankovsky, Nikolay Myaskovsky, Czecho-Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra (Bratislava) MYASKOVSKY: Symphony No. 8 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsNot a Minor Composer Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 01/20/2001 (4 out of 5 stars) "It is a shame that Nicolai Miaskovsky (1881-1950) has never really been granted his due in the West. Between Alexander Glazunov and Sergei Prokofiev, Miaskovsky ranks as the most important Russian composer; he was arguably the first Soviet composer, although his Sixth Symphony (1924), with a choral Finale, invokes "God" and generally strays from Marxian political orthodoxy. With Shostakovich and Prokofiev, he fell victim to the artistic condemnations of "Zhdanovschina" in 1948. Like Shostakovich and Prokofiev, Miaskovsky could write Stalinist oratorios on demand, as he did in the gargantuan work "Kirov is with Us" in 1942. (Kirov, the Party-boss of Leningrad, was killed on Stalin's orders in 1934 and the government then blamed his murder on an entirely fictitious internal anti-Soviet conspiracy; Stalin then used the claim of this conspiracy to justify the show-trials of 1936 and the attendant mass-executions.) But Miaskovsky also perseveringly sustained a private musical vocabulary, close to that of the exile Rachmaninov, that flouted the prescriptions of musical Socialist-Realist art. His symphonies (all twenty-seven of them) tend to unfold their arguments in the minor key; they also eschew grandiosity of the politically correct kind and suggest the bourgeois sins of "subjectivism" and "cosmopolitanism," guilt in which the Party twice accused him (in 1936 as well as in 1948). Bourgeois and subjective he undoubtedly was and perhaps even a bit cosmopolitan. Like Rachmaninov, he had a fondness for Poe, and at least one work, the tone-poem "Silence" (1911), takes its inspiration from the Baltimore literatus. Quite apart from the terrible context in which he lived and worked, who else in the twentieth century (except Alan Hovhaness) wrote twenty-seven symphonies? In this alone Miaskovsky exercises a pull on curiosity. Individual symphonies have been sporadically available on LP and CD. The conductor Yevgeny Svetlanov supposedly recorded all twenty-seven for Melodiya, but only a few of these have seen the light of day. The closest thing to a cycle comes from Marco Polo, who still list Symphonies Nos. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 12 in their catalogue; the sadly suspended Classical Revelation label had issued Nos. 1, 2, 5, and 22 - the first three with Rozhdestvensky and the last with Svetlanov - before ceasing business. That adds up to about a third of the full sequence. Ages ago, on badly pressed Melodiya export-LPs, I owned Nos. 21, 25, and 27. Why bother? Because Miaskovsky's deeply melancholy response to the disaster of the Soviet Union and to Stalin's tyranny produces a dark music as genuinely pathetic, if not quite as modern or ironic, as that of Shostakovich. Symphony No. 8, although ostensibly in A-Major, is nevertheless preoccupied with minor modes. It follows a program having to do with the Cossack uprising against Polish rule in Ukraine in the seventeenth century; Miaskovsky almost certainly appended the program as an afterthought, to satisfy official strictures. Miaskovsky spins out one beautiful Russian melody after another, mostly in slow tempi, but with much energy in the Scherzo. The centerpiece is the slow movement (Adagio), a nocturne in feeling, with a lovely part for the solo horn, whose material the composer quietly develops over a sixteen-minute span. Robert Stankovsky led the (then) Czecho-Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra of Bratislava in this 1989 performance. One must call it convincing, as no comparison exists to refute the claim. The sound is satsfactory - a bit distant and slightly boxed in as many of the early Marco Polo recordings were."

|

Track Listings (4) - Disc #1

Track Listings (4) - Disc #1