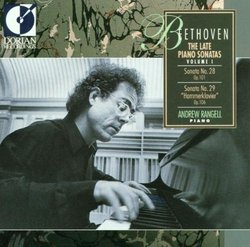

| All Artists: Beethoven, Andrew Rangell Title: Late Piano Sonatas Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Dorian Recordings Release Date: 8/31/1993 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Forms & Genres, Sonatas, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Romantic (c.1820-1910) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 053479014320 |

Search - Beethoven, Andrew Rangell :: Late Piano Sonatas

| Beethoven, Andrew Rangell Late Piano Sonatas Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsVery personal playing from a pianist who deserves his cult s Santa Fe Listener | Santa Fe, NM USA | 04/02/2010 (4 out of 5 stars) "The American pianist Andrew Rangell, born in Chicago in 1948 but apparently living in the UK, has been a coterie favorite for years. I never kept track of him and only vaguely remembered his early Ives recordings. He was afflicted with severe nerve and muscle problems that sidelined his career in 1991. Dorian released this first volume of late Beethoven in 1992, presumably recorded before the onset of Rangell's difficulties, which were crippling for a while but not permanent. The recorded sound is very fine, as you expect from Dorian, which gives this coupling of Op. 101 and the Hammerklavier a leg up -- there's no clatter or hard edge even in the most tempestuous parts.

From the soft, subdued opening of Op. 101, one is reminded of Ivan Moravec, another gentle coterie favorite. The danger with such personal styling is that it can become much of a muchness, or that one loses a sense of rightness. I felt that the first movement moved too much in both directions; Beethoven isn't Chopin, however reflective a pianist wants to be. But the Scherzo comes back into focus and sounds right; here Rangell's thoughtful, low-key phrasing spoke to me. Like Moravec, his touch is soft-grained -- don't expect Serkin's heroic assertiveness or Richter's stormy assaults. Rangell untangles the balled yarn of Beethoven's textures and makes the strands clear for the ear. No wonder he has a doctorate in piano from Juilliard. The overall effect isn't as dry and analytical as it is with Charles Rosen, say, another intellectual pianist. The short, pondering bridge to the finale is done with sober simplicity. In his effort to keep every voice in the final fugue clear, Rangell turns a bit didactic and deprives us of the thrilling pile-up that this movement can deliver. Rangell's Hamemrklavier is cut from the same cloth. The first movement benefits from his way of clearing out the underbrush, and it's blessedly free of Sturm und Bang. Yet the Scherzo isn't sparkling enough, and the application of rubato, as I feared, became much of a muchness (I have the same reservation about Moravec in long stretches). The great surprise, though, comes in an Adagio extended to 24 minutes, where Schnabel takes 18 min. and Pollini 17 min. But Rangell knows his strengths, and I found that his lingering worked, thanks to an intuitive gift for phrasing a long, slow line. Others may find the movement static. In the fugal finale Rangell is stronger than at the end of Op. 101, but he's still careful to dissect and tease out each strand. I was happy to hear the music approached this way, only occasionally missing the titanic heroism that can be found here. In all, a successful, highly personal program that brought considerable rewards." |

Track Listings (9) - Disc #1

Track Listings (9) - Disc #1