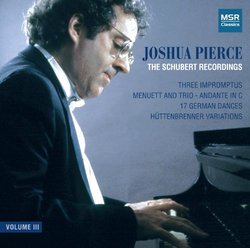

| All Artists: Joshua Pierce Title: Joshua Pierce: The Schubert Recordings - Volume III Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: MSR Classics Original Release Date: 1/1/2010 Re-Release Date: 3/9/2010 Genres: New Age, Classical Style: Instrumental Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 681585120620 |

Search - Joshua Pierce :: Joshua Pierce: The Schubert Recordings - Volume III

| Joshua Pierce Joshua Pierce: The Schubert Recordings - Volume III Genres: New Age, Classical

In Schubert's day, the piano, barely emerged from the shadow of the harpsichord, had two very different personalities. It was the instrument of a whole generation of flashy public virtuosi out to impress the public with f... more » |

Larger Image |

CD Details

Synopsis

Product Description

In Schubert's day, the piano, barely emerged from the shadow of the harpsichord, had two very different personalities. It was the instrument of a whole generation of flashy public virtuosi out to impress the public with flying-finger fantasias and sets of variations on popular tunes of the day. But there was a piano in every parlor, a young lady or poetic young man at every keyboard and a whole new repertoire of songs, songful piano pieces and dance music to suit. It was of course, this latter kind of music at which Franz Schubert excelled. The German word Hausmusik translates very nicely into "house music" and, while the tradition of music-making in the middle European middle-class home would certainly have developed without him, it was Schubert who took hausmusik to its first great artistic heights. It would, of course, be easy to think of Viennese hausmusik as a well-mannered pastime of the bourgeoisie but Schubert's own home life was anything but well-mannered or conventionally bourgeois. He was, in fact, an early example of what would nowadays be called a Bobo a Bourgeois Bohemian. He spent most of his brief adult life in a reprobate society of artists and ne'er-do-wells that was marked by excess sexual, alcoholic and otherwise. Much of the time, Schubert did not even really have a proper home of his own; he spent his time hanging out with his pals and sponging off them. In return for friendship, love and material assistance, he became their musical muse. This was not a small matter; song and dance were essential elements of their life-style. Schubert was one of those Mozartian-style prodigies from whom music flowed in seemingly endless quantities. On any and all occasions, our hero simply sat at the piano and spun out whatever kind of music was required. Fortunately, this stream of music, much of it originally improvised, quickly came to take on definitive notated form. Some of it was even published and performed in the piano parlors of a less bohemian Vienna. Although the stories of Schubert's poverty and presumed neglect are legion, he was in fact highly appreciated in his own circle and, if he had managed to survive longer, he would certainly have become a celebrated and successful composer in his native town. After his death, enough manuscript music was discovered to keep publishers and performers awash in new Schubert works for years; how much was lost we ll never know.

Track Listings (38) - Disc #1

Track Listings (38) - Disc #1