A Serious Case of Cello Envy!

Giordano Bruno | Wherever I am, I am. | 09/13/2009

(5 out of 5 stars)

"I suppose all bassoonists suffer cello envy at times. It's not brought on by dissatisfaction with my beloved bassoon. Hey, I can play all the same notes and just as fast, though I haven't yet figured out how to imitate 'double stops' on a single reed. Part of the envy is the repertoire; for every splendid bassoon concerto, there are ten splendid cello concerti, not to mention the ineffable repertoire of the string quartets and quintets. But there's also the freedom of stage-presence. A cellist can smile, gape, sneer, lip-synch, gnash teeth; shake her/his head expressively; waggle or shrug shoulders. A cellist can make much of dramatic flourishes of the bow and the bowing arm. If I did any of those things, I'd be blowing 'clams' and squeaks; my face is partly hidden, partly frozen. I've just recently backed up -- literally, about three meters in back -- a certain well-known wild-haired wraith-like British cellist in a performance of the Haydn C-major cello concerto. I couldn't see his face, but the guy put on a show with his arms, flinging them wide, waving his bow in approbation at the orchestra, swaggering with his shoulders. If there were a professor of wizardly music at Hogwarts, he'd have the job.

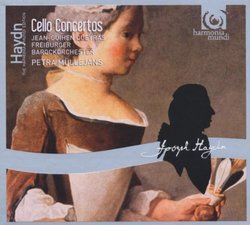

Jean-Guihen Queyras, the cellist on this CD, makes less of a physical impression on stage. He often plays with his eyes closed and with his face merely a trance-like glow. All the energy goes into the bow and the fabulous fingers of his left hand on the neck of the cello. What he does with that left hand on the 'Finale-Allegro molto' of the C-major concerto is super-human, a level of sinisterity (in lieu of dexterity) unmatched by anyone. The low notes than he digs out of the lower strings of his cello are seismic in timbre and perfect in intonation. His tone doesn't get whiney as he scrambles 'up' the scale toward the alto register. Yes, he's playing a 'period' instrument, a cello strung as it would have been strung in the mid 18th C, but don't expect any 'apologetics' for the sake of authenticity. Queyras technically outplays any modern cellist on any recording. Combine that with the sensitive 'historically informed' performance of the Freiburger Barockorchester and you have a CD you'll want to hear often for the rest of your life.

Haydn's C-major Cello Concerto #1 was rediscovered in Prague in 1961. Since then it's become a staple of the repertoire. Haydn wrote it some time before 1765, when he was about thirty years old and in his early years at Kapellmeister at the Esterházy court. Ludwig van Beethoven was some five years short of birth at the time. (He was born in 1770. After you listen to Haydn's cello masterpiece, perhaps you'll form a notion of why I mention these dates.) Haydn's Second Cello Concerto in D-major was written and performed in 1783, roughly twenty years later. The two works are consummate summations, the first a consummate retrospective of the evolution of the Baroque concerto, the second a prescient musical vision of the potential of the concerto form to express the full spirit of the classical>romantic future.

The culminating moments of both concerti come in the several extended cadenzas -- passages for the cello alone, the whole orchestra awed, with bated breath, as the cellist displays his maximum virtuosity. These cadenzas, as played by Queyras, are more than musical gymnastics. They are powerfully emotional monologues. Since I'm not a cellist, I haven't seen the scores and I don't know how much of the cadenzas Haydn wrote out or how much has been left to the performer's musical imagination. Cellist readers, you might be so kind as to educate me. In any case, the cadenzas as recorded are the musical equivalent of seeing a trumpeter swan or riding a surf board for the first time.

The third concerto on this CD, by Georg Matthias Monn (1717-1750) is more than just a disk-filler. It's a charming energetic composition, structurally close to Vivaldi but already managing to sound like a work of the Viennese Classical school. It's the only Monn composition you're likely to hear, and that fortuitously, since Arnold Schoenberg approved of it and included it in his editing of the "Monuments of Austrian Music" in 1912.

Can I make this the Bruno 'pick of the month' for November, or would that be cheating?"