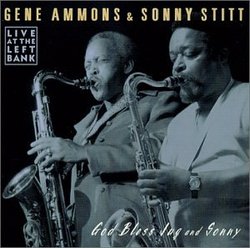

| All Artists: Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt Title: God Bless Jug & Sonny Members Wishing: 3 Total Copies: 0 Label: Prestige Original Release Date: 1/1/1973 Re-Release Date: 8/7/2001 Genres: Jazz, Pop Styles: Soul-Jazz & Boogaloo, Bebop Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 025218311922 |

Search - Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt :: God Bless Jug & Sonny

| Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt God Bless Jug & Sonny Genres: Jazz, Pop

|

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs

|

CD ReviewsChristagau's review informs us 09/10/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "Tenor battle in which two saxmen blow each other's brains out .... live CD-released 2000, recorded 1973. The Baltimore crowd brings out the brawler in both Albert's boy Gene, with his woogie-steeped r&b tendencies, and the famously facile Stitt, known for his eagerness to replicate Bird solos and cut [lousy tracks]in the studio for cash on the barrelhead. The combat is friendly and uncerebral-Stitt pushes Ammons's big gruff Hawkins chops toward modernism as Ammons drives Stitt to a raucous showboat bebop that keeps on churning as tracks approach the quarter-hour mark. Cedar Walton, Sam Jones, and the incomparable Billy Higgins are so fluid you hardly mind when the leaders sit out for a Walton feature, and the 2002 sequel is almost as good even though two Etta Jones vocals intrude. Called Left Bank Encores, it was cut the very same night." Jug and Sonny "vamp" their way to success? Herbert L Calhoun | Falls Church, VA USA | 09/27/2009 (2 out of 5 stars) "Ammons about said it all on his album "Hitting the Jug." [Really, what else is there left to say about his version of the blues after that album?] Thus its difficult to get inspired when he is in the "showboating mode," as is the case here. Usually he is pushing Stitt away from Stitt's own "smug" academic impression and interpretation of "Bird," towards a more earthy bluesy sound. [Can you even imagine what an earthy Sonny Stitt would sound like?] Here, they both go for crowd pleasing. And on that score they are a success. But for a "purest" (and in the context of their best work) these "mercenary displays" have a hollow musical ring to them, for they tend not to be about the business of pushing the music to new brighter frontiers. Even though admittedly lively and energetic, it seems that both Jug and Sonny are here stuck in the 60s "comp," "vamp" and "honk" mode. Its not a pretty picture musically for two giants of their era. But hey, everyone has to make money. Two stars" Admittedly for completists, but let's set the record straigh Samuel Chell | Kenosha,, WI United States | 03/29/2010 (3 out of 5 stars) "I didn't notice that "God Bless Jug and Sonny" was another recording in the "Live at the Left Bank" series, or I would not have ordered it. Previous editions in this series, including one under Stitt's sole name, are essentially unlistenable due to bad mic placement and/or mixing, highly problematic balance, and frequent distortion (though "Sonny Stitt at Ronnie Scott's" is even worse, the poorest excuse for a bootleg even though it's still peddled on eBay and, last I looked, Amazon--moreover, by now it's public domain and put out on any number of labels under different titles. Just watch out: a rip-off by any other name is still a rip-off.

Producers of the Stitt-Ammons sessions have tended to prey upon (understandably) human emotions and sympathies attached to either or both players. So we have Jug's very final session, "Goodbye," which cannot be recommended either as a recording doing him justice or as a satisfying session. And only slightly better than any of the aforementioned is the Ammons-Stitt date "We'll Be Together Again." As for "God Bless Jug and Sonny" the audio is tolerable but does not flatter either player, putting each excessively forward in the mix and on the very edge of distortion. Jug, whose huge sound was usually joyful and uplifting, sounds forced and grating on this recording, as occasionally does Sonny (but not on alto). This was a year before Jug's passing, a time when he was hurting in several respects--with financial, health, and employment problems. It was a time when the happening thing was fusion, whether Miles' electric bands or the nascent ones about to be formed (Weather Report, Corea, Herbie)--or, at the other extreme, it was acoustic players taking after the post-"Love Supreme" Coltrane into primal scream territory, altissimo registers of musical / incantatory exhalations resisting, and unworthy of, any labeling, whether jazz, free, fusion, world. Jug felt the pressure acutely, began to struggle to find work, and admittedly was a disappointment several of the times I caught him live in the seventies. He would occasionally abandon that rich, distinctive, soulful sound (he once recorded an album of straight hymns with his church organist) in favor of strident screeching and even tasteless multiphonics. And when he would take it back "inside," the strain was frequently evident in terms of bad intonation. Sonny might follow him into the outer zones for a brief moment, but he always came back to his game, whether Parker bebop or inner-city lounge-jazz blues. He's actually in immaculate form on this recording, playing all of the licks I know by heart but playing them better than could anyone else (on "Stringin' the Jug" try to ignore everything except Sonny's facile, head-spinning solo and unequalled technique--familiar or not, it's a privilege to hear jazz' "Lone Wolf" operating at maximum efficiency). As for the previous reviewer's characterization of this recording as commercial, or "money music," and of Sonny Stitt as "smug" and "academic," nothing could be further from the truth. Both of these musical giants were hurting financially throughout much of the 60s and 70s--not because Bird and bebop had worn out their welcome but because there were few listeners left who could actually 'hear it," or, for that matter, even find anything of worth among the standards comprising the so-called "Great American Songbook." I was more than a little taken back on one occasion when Sonny's drummer, Billy James, described to me how tough it was merely to make ends meet working with Sonny, especially when neither worked daytimes as college professors or chairs of jazz departments. It was strictly week by week, and without any "benefits." On another occasion, I was heartbroken to hear, from a protege of Jug's, about the tenor giant's last grim days as he fought, valiantly and unattended, a virulent cancer. Sonny never acknowledged indebtedness to Charlie Parker because I frankly believe him when he said they arrived at similar styles coincidentally (and not that far apart from one another in time). Sonny was as gifted a saxophonist as Bird (maybe more so), though undeniably not as creative or innovative (he was in some respects a "more accessible Bird"). But there's one quote of Sonny's that is perhaps more telling than any other: when pushed by an interviewer about not being more adventurous--more willing to explore "modal" and freer, less "harmonically restrictive" forms--he somewhat uncharacteristically lost his patience and snapped back: "What's wrong with you? As a musician, my job is to keep it simple and entertain people. Look at Art Tatum. Who was any better than him? Yet he kept it simple and played so people could understand him." (Sonny, I know for certain, was not being intentionally ironic.) If that's a "smug academic," we could use more just like him. Unfortunately (or, fortunately, for those of us who were on the scene), there was only one." |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1