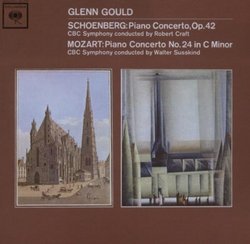

| All Artists: Glenn Gould Title: Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 24 in C Minor Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Sony Bmg Europe Release Date: 9/3/2007 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 886971476521 |

Search - Glenn Gould :: Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 24 in C Minor

CD Details |

CD ReviewsGould's Only Mozart Piano Concerto... Sébastien Melmoth | Hôtel d'Alsace, PARIS | 02/03/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) ". This 1962 reading of Mozart's twenty-fourth Piano Concerto (K. 491, c-minor) is the only Mozart piano concerto GG ever performed and recorded. Gould's biographer Kevin Bazzana calls it "surprisingly powerful." Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould In keeping with Classical performance practices, GG extemporizes the cadenza in Movement I--virtually writing his own as he had done with Beethoven's First Concerto. The orchestral soloists are very good here, and miked well for clear enunciation. Gould writes, "It is the last movement which holds the Mozart of our dreams. Here, in a supremely beautiful set of variations, is a structure in which as variation upon variation passes by, the chromatic fugal manner which Mozart in his philosophic moods longed to espouse is applied with brilliant success." ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ GG had championed Schönberg's Piano Concerto (Op. 42, without key signature) as early as 1953 when he first performed it in public. Here realized under the baton of the always-fine Robert Craft, Gould provides an "unabashedly Romantic" revelation. The recording itself is miked very closely and as a result is quite "dry." ." UNUSUAL IN MORE WAYS THAN ONE DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 03/21/2008 (4 out of 5 stars) "`Interesting' might be the safest word to categorise this disc. To start with three points that are beyond argument - the total playing time amounts only to 50 minutes; the liner essay is reproduced in a microscopic typeface; and the C minor is the only Mozart concerto that we have on record from Gould.

Pretty well everything else is a point of contention in one way or another. I say periodically in reviews (and I stand by it) that much of what we read regarding supposed eccentricity in Gould's playing is hugely exaggerated. His general approach to the Mozart concerto is not unorthodox. By way of a comparison from roughly the same era I also played Solomon's recording, which finds Solomon at his best and can be recommended without qualification. Gould's tempi are very much like Solomon's, and his view of the first movement as elegiac in tone rather than sinister like the other great minor-key concerto K466 in D minor is very similar to Solomon's as well. However the slow movement as Gould does it is bound to raise some eyebrows. Gould's famous pearly touch, which in Bach or in Haydn or in early English music is recognisable instantly, seems absent here. The recording (of which more in a moment) may have a lot to do with this, but I had never previously associated Gould with the old-fashioned trick of putting down the left-hand before the right, and that at least can't be the result of the recording. It is an expressive device that I happen to like within limits. Backhaus uses it a lot, Horowitz and Michelangeli somewhat less, and nearer to home we hear it regularly from that prince of Mozart-players Rudolf Serkin. Neither Serkin nor any of the others just named would have used it to anything like the extent that Gould does here, to say nothing of arpeggiating chords, something I can imagine from none of them. Come the finale, we are starting to hear the great Gould sound at last, and in the last variation I heard something downright wonderful. Beethoven said that he could never equal this, and for perhaps the first time I thought I fully understood what Beethoven meant. The recording gave me some problems, but I found I could overcome these to some extent by reducing the volume from the level I usually leave it at. Not entirely, though. The orchestral tutti sound can be a bit coarse even at a lower volume-setting (although by and large it is clear enough). What it may be doing to the soloist I'm not sure. When playing Mozart on a modern grand the great Mozartians scale down their tone. Solomon, whose tone was smallish, still reduces it, and Serkin, whose tone was huge, brings it down to similar dimensions. Some of Gould's left-hand work in the first movement comes over to me as altogether too beefy. I suspect this was partly of his own doing, but the recording does him no favours with an excessively close focus. These issues are less serious in the Schoenberg concerto. Gould proselytised for the second Viennese school, and I already know his work in Webern and Berg. By way of a comparison I replayed my version from Peter Serkin. He is the son of Schoenberg's pupil, he is an eminent exponent of 20th-century music in his own right, and he is accompanied by the LSO under the direction of no lesser a specialist than Boulez. Differences between the two versions are of detail rather than conceptual, although I spotted that Gould gets through the 20-minute work in two minutes less. That makes no difference to me. In fact if I had to give my vote to the Serkin/Boulez account it would be mainly because of the typically sharp focus that Boulez gives to the orchestral work, something I have come to love in his Stravinsky. Good heavens, the liner-note! It has been downsized from the back of an LP and it seems to challenge us to read it in its infinitesimal new form. My own eyesight is still good and I started without assistance, but quite soon I was getting irritated at my slow progress through it and invoked my light-assisted magnifying glass. In case you can't read it, or can't be bothered reading it, it is a learned but distinctly pretentious and opinionated effort, full of statements apparently designed to challenge orthodoxy and/or bring enlightenment to those denied the author's level of insight. Challenging the various propositions put forward would outrun the capacity of a short review. I am not by any means inclined to refute everything the author says, although I must say I would have liked to be told who the author was. The piece is genuinely thought-provoking, and I shall restrict my own comment to saying that the statement attributed to Tovey about Beethoven's failure to master Mozart's technique in the opening orchestral section in a concerto is inaccurate and misleading. Tovey of all people would never have allowed any composer to outshine his revered Beethoven for long or in any serious respects. What Tovey actually said was that Beethoven had not fully mastered the trick in his first three piano concertos but got it right in and with effect from the triple concerto. I found myself more at a loss than usually in trying to give a star-rating to this disc, and the rating I have given presumes a reasonable price for rather a small measure of music. It's an unusual item to some extent, but to what extent, and to how serious an extent, is something I don't feel like trying to assess even for myself let alone for anyone else. It's Gould, of course, he was taken from us too soon, so I shall try to err on the positive side." |