The Glory of Widor and Guilmant

Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 08/05/2001

(4 out of 5 stars)

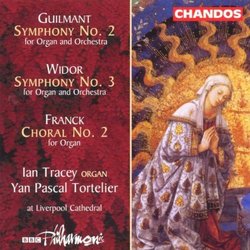

"Charles-Marie Widor (1844-1937) and Felix Alexandre Guilmant (1837-1911) both studied with the Belgian organist-teacher-composer Nicolas Lemmens and both themselves taught, in Paris, at the National Conservatory; they belong to the high phase of the Romantic school in French organ composition, being succeeded by men of a much younger generation such as Marcel Dupre and Olivier Messiaen. The Chandos CD of organ-and-orchestra scores by Widor and Guilamant is a brilliant example of musicological discovery, interpretation, and engineering. The program puts Guilmant's Symphony No. 2 for Organ and Orchestra (1906), comprising five movements, in first place. The adjective "rip-roaring" fits Guilmant's Symphony, which opens with a fanfare-dominated Introduction and Allegro Risoluto and ends, a half-hour later, with a knock-about fugue in mock-Handelian style. There must be at least one more Symphony for Organ and Orchestra by Guilmant, and on the basis of No. 2, I'd like to hear it. Why have audiences been content with Camille Saint-Saens' Symphony in A-Major for so long? Guilmant's essay is just as attractive as Saint-Saens' and it boasts the advantage of being new to us. The same goes for Widor's Symphony No. 3 for Organ and Orchestra (1896), in two movements running in total slightly over a half-hour. Widor's score is less like a concerto than Guilmant's, letting the organ infiltrate the texture slowly in the First Movement (Adagio - Andante - Allegro) and giving it center-stage only in the last part of the Finale (Vivace - Tranquillamente - Allegro - Largo). Unlike the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra Opus 42 (a.k.a. No. 1), which reworks movements from Widor's symphonies for solo organ, Symphony No. 3 appears to be an entirely new composition. What impresses one about Widor's music, in whatever genre or for whatever medium, is its unflagging confidence, its directness of gesture, its mastery of the forms. Were organ music not so thoroughly identified with the church, Widor (and his successor Louis Vierne) might today enjoy wider currency than they do. The Symphony No. 3, for example, is as good a symphony as anything written in the same genre, say, by Vincent d'Indy or Guy Ropartz; its moments of sobriety convey great dignity and its moments of display thrill all the way down to the marrow. The galloping development section in the First Movement calls to mind Cesar Franck's tone-poem "Le chasseur maudit." The slow music two thirds of the way through has an Elgarian nobility to it. Widor casts the peroration (Largo) that brings the Second Movement to its conclusion in the same triumphal character as the corresponding passage in Franz Liszt's "Hunnenschlacht." Widor's organ-and-orchestra works are gradually being rediscovered and restored (thanks to the compact disc) to the recorded repertory: The Symphony Opus 42 and the Sinfonia Sacra can be had on discs issued by the Motette label. The organ soloist on the Chandos program is Ian Tracey. Yan Pascal Tortelier leads the BBC Philharmonic. This is a great disc for baffling one's friends. "Guess who wrote this?" Another rewarding program of organ-and-orchestra music also appears on Chandos - this one of works by Japanese composers, two of which (Atsutada Otaka's "Fantasy" and Toshio Hosokawa's "Memories of the Sea") are in fact, if not in name, symphonies for organ and orchestra. Chandos has become a byword for demonstration quality engineering and they do themselves proud in recording Guilmant and Widor. The disc closes with Franck's Choral No. 2 for Solo Organ. Could the producers not have found a another score for the same forces required by Guilmant and Widor? In any case, the disc is a wonder and should be considered for swift purchase by anyone with an interest in late Romantic music."