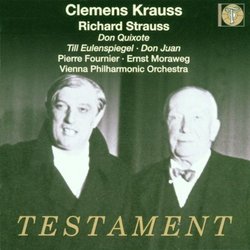

| All Artists: Strauss, Fournier, Vianna Phil Orch, Krauss Title: Don Quixote/Don Juan/Till Eulenspeigel's Merry Pranks Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Testament UK Release Date: 9/12/2000 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Style: Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 749677118525 |

Search - Strauss, Fournier, Vianna Phil Orch :: Don Quixote/Don Juan/Till Eulenspeigel's Merry Pranks

| Strauss, Fournier, Vianna Phil Orch Don Quixote/Don Juan/Till Eulenspeigel's Merry Pranks Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsStrauss Played Straight by His Friend Krauss, Not in Stereo Doug - Haydn Fan | California | 11/12/2009 (4 out of 5 stars) "These recordings made near the end of Clemens Krauss's life - the Don Quixote was made in 1953 and he died the next year on tour in Mexico - are part of a group of Strauss works Krauss recorded for Decca after the war with the Vienna Philharmonic. Sadly, they were made just a few years before the advent of stereo - part of the reason I give them only four stars. With that said, the Decca engineers did the best they could under less than ideal circumstances - the old recording venue having been bombed during the war. To my ear the two shorter works fare better sonically, while the longer, more complex recording challenge of Don Quixote, with its prominent roles for soloists, fares less well, sounding at times cavernous. The performances can be summed up succinctly - Til and Don Juan receive relatively mainstream readings, but Krauss approaches Don Quixote with a wider mixture of elements, from humorous links to previous works of Strauss, to a trace of, if not tacituntiy, certainly more reticence than I've heard in this music.

Indeed, excellent as the other performances indeed sound, it's the Don Quixote which lingers. Krauss makes clear from the first that this Knight of the Woeful Countenance is related by blood to the lusty youth Til Eulenspiegel, even as he allows cellist Pierre Fournier to present an introspective, somehwat craggy take on the poor old Don. Krauss allows his solists an inordinately out of balance prominence - out front and center stage to a great degree - perhaps partly he nature of the recording venue. There is a certain deliberate downplaying of the orchestra forces natural proclivities to run a bit amok in the great Strauss fortes, Krauss keep a short chain on the massed beast always threatening to spring into the fray and dominate the action. Of course, there ares till moments of glory when the Don runs into problems, and the bleeting sheep are great, but the care Krauss takes with the wind machine section, his insistence the strings swell just so and no more, makes clear this Don Quixote will never descend into a cheap orgiastic pandemonium. Overall the elements play second fiddle to Fournier's reflecting quest. The monural sound we hear of his cello takes on a dark, sombre coloring, and this is further reinforced and reflected back in the dark tonalities we hear when the Vienna Philharmonic weighs in for their parts. I've played this recording of Don Quixote now three times, and it still baffles me a bit. Krauss was said to approach Strauss's music much as the composer does, more direct and no nonsense, without all the excessive flamboyance often heard in this music. Compared to the other versions of this music, even the relatively low-keyed version with Kempe, Krauss's vision of this wonderful music remains far and away the driest, the one where the conductor's role at playing God is least noticeable. Of all the many performances I've heard, on records and in conceert, Krauss's Don Quixote is the trickiest to describe, the most ineffable. The Testament team have done an excellent overall job with this issue - my first chance to hear this performance was on a electonically touched up Lp, with phony stereo. This version, by contrast, is clear and unclouded by artifical 'improvements'. Included are several pages of notes - in very small Cd type - throughly documenting Krauss's entire career, and taking time to elaborate his close working relationship with composer Strauss. There are other Krauss recordings of Richard Strauss reissued by Testament, I have one other, including Also Sprach. Historians of conducting, and Richard Strauss fanatics should find this issue of interest. For most people you might want to look elsewhere for these Strauss pieces. I think there are more than enough alternatives, some better performed, in stereo - a must in this music. " |

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1

Track Listings (16) - Disc #1