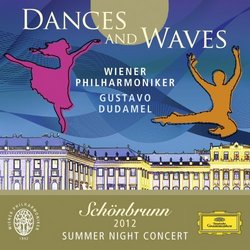

| All Artists: Gustavo Dudamel, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin, Claude-Achille Debussy, Richard Georg Strauss, Amilcare Ponchielli, Johann Strauss II, Geronimo Gimenez, Wiener Philharmoniker Title: Dances & Waves: Schoenbrunn 2012 Summer Night Concert Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Deutsche Grammophon Release Date: 8/21/2012 Genre: Classical Style: Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 028947647171 |

Search - Gustavo Dudamel, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky :: Dances & Waves: Schoenbrunn 2012 Summer Night Concert

| Gustavo Dudamel, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky Dances & Waves: Schoenbrunn 2012 Summer Night Concert Genre: Classical

A soirée is in full swing, the assembled company enjoying itself immensely and dancing a polonaise. Only one of the guests stands apart, Eugene Onegin, the opera s hero or, rather, the anti-hero of an anti-opera... more » |

Larger Image |

CD Details

Synopsis

Product Description

A soirée is in full swing, the assembled company enjoying itself immensely and dancing a polonaise. Only one of the guests stands apart, Eugene Onegin, the opera s hero or, rather, the anti-hero of an anti-opera that Tchaikovsky wisely described not as an opera at all but as a series of Lyric Scenes . Here the golden rules of the theatre seem to have been cast aside in favour of a bold attempt to bring Pushkin s Eugene Onegin to life on the operatic stage, an attempt all the more remarkable in that the Russian poet s verse novel has always been regarded as a national treasure. But Tchaikovsky overcame every doubt, including his own. The drama stems from the music, and the orchestra alone is aware of the emotional depths of which St Petersburg s partying high society remains wholly unsuspecting. This final act ends badly for the chronically bored Onegin, a dandy and a ladies man spoilt by success. Even the polonaise portends disaster for him, progressing with an implacable majesty as inevitable as the fate that is soon to prove the undoing of the burnt-out bon vivant. All of Tchaikovsky s works, be they operas or symphonies, deal with this hostile force of a superior destiny.

The Russian composer was possessed by a positively paranoid belief in fate, seeing it at work wherever he looked, even in parties and balls and a baleful polonaise. But whereas Tchaikovsky needed only the circumscribed world of landowners, aristocrats and members of the officer class for his metaphysical social dramas, his two fellow countrymen Modest Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin wrote their amorphous unfinished operas against a broader historical background that encompassed a vast panorama of Russian history, geography and culture. Borodin spent almost two decades struggling to find the right form for an opera based on the medieval Lay of the Host of Igor, an early Russian heroic epic that he tried to adapt as both librettist and composer, deliberating at length on matters of music and dramaturgy but without ever coming to a definitive conclusion. When he died in his native St Petersburg in 1887, Prince Igor his self-styled Russian epic opera was still incomplete, a rough-hewn structure still full of numerous holes.

Mussorgsky s Khovanshchina described by its composer as a national music drama likewise remained unfinished, surviving in the form of a convolute of manuscripts written down between 1870 and 1880. The composer s own libretto takes as its starting point the period leading up to the accession of Peter the Great and centres on the uprising and overthrow of the Strel tsï, the crack Moscow militia under Prince Ivan Khovansky, who gives the opera its name. Normally translated as The Khovansky Affair , Khovanshchina could also and more colourfully be rendered as The Khovansky Mess . In 1879, the year in which Eugene Onegin received its first performance in Moscow, excerpts from Prince Igor and Khovanshchina were performed at a series of workshop concerts in St Petersburg, including the Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor. (The Polovtsians are pagan nomads who have captured our eponymous hero.) Khovanshchina was represented by the Dance of the Persian Slaves performed in the opera as a way of bewitching Prince Khovansky before he is assassinated. In both cases we are dealing with musical varieties of orientalism, colourful, magnificent and martial in Borodin s case, mysterious and melancholy in Mussorgsky s. This exotic element is an integral part of the Russian nationalist school, an aspect of the country s cultural identity under Tsarist rule, when Russia s imperialist ambitions extended towards the East.

Richard Strauss, conversely, sought the Orient not in remote continents but deep within our unconscious, in the topography of the human psyche. Completed in 1905

The Russian composer was possessed by a positively paranoid belief in fate, seeing it at work wherever he looked, even in parties and balls and a baleful polonaise. But whereas Tchaikovsky needed only the circumscribed world of landowners, aristocrats and members of the officer class for his metaphysical social dramas, his two fellow countrymen Modest Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin wrote their amorphous unfinished operas against a broader historical background that encompassed a vast panorama of Russian history, geography and culture. Borodin spent almost two decades struggling to find the right form for an opera based on the medieval Lay of the Host of Igor, an early Russian heroic epic that he tried to adapt as both librettist and composer, deliberating at length on matters of music and dramaturgy but without ever coming to a definitive conclusion. When he died in his native St Petersburg in 1887, Prince Igor his self-styled Russian epic opera was still incomplete, a rough-hewn structure still full of numerous holes.

Mussorgsky s Khovanshchina described by its composer as a national music drama likewise remained unfinished, surviving in the form of a convolute of manuscripts written down between 1870 and 1880. The composer s own libretto takes as its starting point the period leading up to the accession of Peter the Great and centres on the uprising and overthrow of the Strel tsï, the crack Moscow militia under Prince Ivan Khovansky, who gives the opera its name. Normally translated as The Khovansky Affair , Khovanshchina could also and more colourfully be rendered as The Khovansky Mess . In 1879, the year in which Eugene Onegin received its first performance in Moscow, excerpts from Prince Igor and Khovanshchina were performed at a series of workshop concerts in St Petersburg, including the Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor. (The Polovtsians are pagan nomads who have captured our eponymous hero.) Khovanshchina was represented by the Dance of the Persian Slaves performed in the opera as a way of bewitching Prince Khovansky before he is assassinated. In both cases we are dealing with musical varieties of orientalism, colourful, magnificent and martial in Borodin s case, mysterious and melancholy in Mussorgsky s. This exotic element is an integral part of the Russian nationalist school, an aspect of the country s cultural identity under Tsarist rule, when Russia s imperialist ambitions extended towards the East.

Richard Strauss, conversely, sought the Orient not in remote continents but deep within our unconscious, in the topography of the human psyche. Completed in 1905

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1

Track Listings (10) - Disc #1