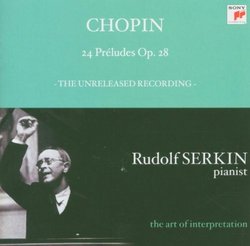

| All Artists: Frederic Chopin, Felix [1] Mendelssohn, Rudolf Serkin Title: Chopin: 24 Préludes, Op. 28 (The Unreleased Recording) Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Sony Bmg Europe Original Release Date: 1/1/2005 Re-Release Date: 7/18/2005 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Style: Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 |

Search - Frederic Chopin, Felix [1] Mendelssohn, Rudolf Serkin :: Chopin: 24 Préludes, Op. 28 (The Unreleased Recording)

| Frederic Chopin, Felix [1] Mendelssohn, Rudolf Serkin Chopin: 24 Préludes, Op. 28 (The Unreleased Recording) Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsNEW! DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 09/16/2005 (4 out of 5 stars) "This is a turnup for the book, and no mistake. By 1976 Serkin had long given up playing Chopin in public, but I ought to have known about this recording because there it is, clear as daylight, among the unreleased items listed in the excellent biography by Stephen Lehmann and Marion Faber. He was a terrible old stick-in-the-mud for refusing to issue his solo recordings in his later years, and I am familiar with the process that had to be gone through to get some of his Beethoven sonatas made available to us. I suspect that I had forgotten about this Chopin recording from the same period because I never seriously expected to hear it.

I believe I actually own the grand total of Serkin's other Chopin that can currently be purchased. It consists of the op 25 studies contained on the disc that comes with the biography, and also of two of these same studies on an unauthorised production from 1932/3 entitled `Great Musicians in Copenhagen'. These are by the young Serkin, of whom the septuagenarian partly disapproved, but no deficiency in the recorded quality can conceal the fact that here we have a superb Chopin stylist. In his later Beethoven I have always felt that while something was gained more was lost, but in Chopin to my surprise I'm inclined to think that the balance is much more equal in those ways. Some particularly attractive playing on this disc shows the most un-Serkinesque characteristic of being relaxed -- neither in commendation nor in censure have I often, or ever, seen him called that. The second last of the preludes is absolutely delightful in this respect, and so are # 11 in B and # 17 in A flat. There is something of the same feeling about the E flat, although of course that has its formidable side with those tolling notes in the deep bass as well, but one reading that has started to appeal to me strongly since a second hearing is the third number in G, taken at less of a helter-skelter than we usually hear and none the worse for that. By this stage I should make clear that the shortcoming of this disc is the recorded sound. This is definitely too resonant, and that is an enormous pity considering how good the sound is on Serkin's Beethoven recordings from the same general period. In fact even at a first hearing it suits some of the numbers really very well. The first prelude is very effective indeed in this kind of sound, although I bet it would surprise many an experienced listener when he or she found out who is playing. I have owned for many years two other performances of the preludes, from Arrau and from Pollini, and of these Pollini has been much more to my general taste for his lighter touch. A first hearing inclined me to think that Arrau's exact contemporary Serkin was going to be in a similar mould (and indeed the B minor, # 6, is probably a bit professorial), but a second and then a third hearing, now that my ears are starting to attune to the recording, are beginning to disclose more affinities with Pollini and fewer with Arrau. Nothing from start to finish is what I would call perverse or even unusual to any great extent, although as throughout his life Serkin separates his hands in the lyrical sections of the D flat prelude that goes by the wretched sobriquet of `raindrop'. Speeds are very normal in general, and the B flat minor is played in much the time and in much the same way as Pollini does it, not raced through in 1 minute flat as by Arrau and definitely taking the right-hand work in the first part of the piece as melody and not as `pianism'. The strange second prelude is a little more mouvemente than I'm used to, Serkin carries off the E major more simply and to my ears more naturally than do Pollini and Arrau, and the last of all is a mighty reading with the tempo superbly judged, even in this recorded sound. The unexpected and welcome nature of this production has even had me inspecting some of the more arcane controls on my cd-player, heretofore untouched by human hand, to see whether I may be able to dry out some of the otiose resonance and get a bit closer to what I imagine the genuine sound may have been like. As a bonus we have a prelude and fugue by Mendelssohn, the same work I believe as I once heard from Serkin in London. No virtuoso ever made his or her name as a player of Mendelssohn, but Serkin probably did more than any recent player to rescue the piano concertos from comparative oblivion, and you can hear some superlative work from him in the Songs Without Words on the `biography' disc. This is an interesting piece, (although I suspect it deserves Tovey's strictures directed at Mendelssohn for impure and unmethodical counterpoint in his fugues), and unsurprisingly it is very well done. All in all, this disc has come as something of a bolt from the blue to me. As a systematic collector of Serkin's work I welcome it in particular, but I even suggest that once your ears have adapted to the special sound you may conclude that this is a notable issue of the Chopin preludes from any point of view. How long this centenary series will remain on the market is something I have no way of knowing either." |

Track Listings (26) - Disc #1

Track Listings (26) - Disc #1