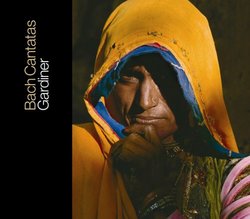

| All Artists: Joanne Lunn, Robin Tyson, Daniel Taylor, Chrisoph Genz, Brindley Sherratt, Gotthold Schwarz, The Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, John Eliot Gardiner Title: Cantatas, vol. 5 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Soli Deo Gloria Original Release Date: 1/1/2008 Re-Release Date: 11/11/2008 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 843183014729 |

Search - Joanne Lunn, Robin Tyson, Daniel Taylor :: Cantatas, vol. 5

CD Details |

CD ReviewsSublime Music--Outstanding Interpretations Johannes Climacus | Beverly, Massachusetts | 02/10/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "Gardiner's Bach Cantata Pilgrimage series continues with a clutch of cantatas that must rank among Bach's greatest contributions to the genre. As usual, Gardiner's interpretations are bristling with insights and creative energy. Sometimes one might wish for a more laid-back approach; but a wee bit of interventionism is better than the blandness one often encountered in the old Kapellmeister tradition of Bach performance. BWV 178 is an ingeniously constructed and intensely dramatic work; it is also (as Gardiner notes in his unusually insightful commentary) formidably difficult to perform. Gardiner's forces are certainly equal to the task, and give of their best. A real tour de force is the astonishing alto recitative in which the soloist sings the chorale in real time accompanied by the same tune in double diminution. Here, as throughout the performance, both singers and instrumentalists are on their mettle. A fine performance, even if Karl Ricther's classic version offers smoother execution and a more sweeping interpretation. BWV 136 is a kinder, gentler work, though it shares a deeply penitential text with its disc-mates. Though neither as compelling in concept nor as tidy in execution as Suzuki's best-ever rendition, Gardiner's performance still manages to convey the muted joy and hopefulness rather well. Solo singing is good, though not quite up to the level of that on the rival Suzuki recording. BWV 45, long a favorite, has recieved many distinguished recordings, including those by Karl Richter and Ernest Ansermet from the early stereo era. They should not be forgotten, if only because the solo singing--though more operatic than many listeners may feel comfortable with today--was so splendid (both Krause for Ansermet and Fischer-Dieskau for Richter eclipse all subsequent competition in the dramatic bass arioso). Gardiner conveys the deep unease at the heart of the work (more in the two arias than in the unexpectedly jubilant-sounding opening chorus) quite as well as his traditional performance-practice forbears, though once again I must note that the solo singing is not quite up to par. The bass soloist, Brindley Sherratt, offends by giving the stiffest and wooliest account I have heard of his great arioso. BWV 46, again one of Bach's supreme masterpieces, commences the second trilogy of penitential cantatas on CD 2. One notices right away the more vivid acoustic of a different church venue, and performances that are more alert overall than those found on the CD 1. Gardiner's rendition of the great opening chorus stresses the dramatic contrast between the elegaic first half (which Bach later used for the "Qui Tollis" of the B-minor Mass) and the minatory fugue which follows. Gotthold Schwartz copes splendidly with the superhuman demands of his stormy Bass aria and the equally demanding trumpet obbligato is dispatched with remarkable virtuosity. Verdict: not superior to Suzuki, but a great success nonetheless. BWV 101 is probably the most harrowing cantata in the Bach canon: a deeply troubling evocation of peril, fire and sword--in both the literal and spiritual senses. Gardiner effectively conveys the work's shifting scenes and moods: from from the whiplash-punctuated operning chorus, a plea for peace amid the turmoil of war, through the tortured tenor aria and incendiary bass aria, to the transfigured sorrow mingled with hopefulness in the great soprano-alto duet. Since this work ranks, in my estimation, among the top half-dozen Bach cantatas, my standards for any rendition are very high indeed. Hitherto I have awarded the palm to Harnoncourt, whose appropriately chilling rendition (eccentricities for once welcome) I never thought could be surpassed by later contenders. But Gardiner has done it, largely due to better ensemble playing, but also to a better-balanced conception of the work. This volume in Gardiner's series may well be worth acquiring just for this splendid performance of a work that has hitherto not received the attention it deserves. Just when you thought it was safe to get up off your knees, Gardiner applies the penitential lash yet again in BWV 102. This is another of Bach's most remarkable cantatas, and Gardiner's forces are fully up to its demands. The complex opening chorus can seem like a patchwork of diverse segments in lesser performances; but not here. Gardiner and his nimbly responsive choir exhale the entire movement as if in a single breath. A uniquely compelling account. However, Karl Richter's version conveys a loftiness, a sense of majesty that eludes Gardiner. Richter could be heavy-handed at times, but I have always found his rendition of this entire cantata riveting. Comparing Fischer-Dieskau's superb account of the Bass arioso with that of Gotthold Schwartz for Gardiner is instructive. Fischer-Dieskau and Richter are at once more animated and more alive to the dramatic potential of the text (one of St. Paul's most scathing denunciations of hypocrisy); Schwartz and Gardiner give a subtler and more subdued account that is just slightly disappointing for those who were expecting more incisiveness. But I shouldn't make too much of such comparisons. Taken on its own terms, Gardiner's conception of the work conveys full involvement and tremendous integrity. To sum up: this is one of the more desirable volumes in Gardiner's estimable series. Despite vagaries of venue, rehearsal time, and so on, everyone seems fully committed to giving these six masterpieces the tender loving care they deserve. There is not a hint of routine in any of these performances, even when the solo singing falls below standards set by the formidable competition in Suzuki's equally outstanding cycle. Even in a recession economy this expensive set must be given an enthusiastic recommendation." The best of Bach Mary E. White | Michigan, USA | 02/27/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "This purchase was the most recent addition to my collection of the Bach Cantatas directed by John Eliot Gardner. The singing is glorious, in part because the group was recording their Bach Cantata Pilgrimage in a succession of churches where Bach had worked. Singing Bach constantly brings one closer to the heart of the music. The result is a sensitive, meaningful performance of this wonderful body of work." ABOVE IT ALL DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 07/01/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "For newcomers to Gardiner's `pilgrimage' project of recording all the Bach cantatas, the virtues of this particular release are the same as those you will find in practically any other volume in the series. The style of interpretation is scholarly and exemplary, the vocal idiom is the right kind for Bach and the instruments are suitable for music of this period, the actual performances are totally assured in the technical sense, the recording is faithful and proportionate, and above all the atmosphere is instinct with love of the music. Any reviewer who has offered notices of a good number of the other volumes, as I have, risks inflicting tedium on regular readers through constant repetition of the same opinions. However there is no way of knowing which item a newcomer will encounter first. The same things just have to be said every time, and of course the tedium is a property of the reviews only, in no way of this celestial music.

The separate volumes are all edited to a common standard. The format is a sort of book, and among my other repetitions I may as well give my usual warning that the discs require care in extracting. Also as usual, there is a long, scholarly and highly personal essay from the conductor, plus a shorter contribution from another participant, in this case a viola player. This latter is rather refreshingly down-to-earth this time, more concerned with accommodation and shopping than with the performing conditions or even the music. What Jane Rogers says about Berlin is interesting. They stayed at one of the new hotels in the east in 2000, and so did I in 2003 or 2004 - the Holiday Inn on the Prenzlauer Allee. Like Ms Rogers I found the streets nearly deserted after dark, but I sensed no danger whatsoever. I even went to Pankow, once the dreaded abode of the Stasi and the Communist Party, and I found it cheerful and an excellent place to shop for bargains. Gardiner's own essay is of the kind those familiar with the series must know very well. As always, it is full of deep, affectionate and often even visionary musings concerning the music, its creator, and his Creator in His turn. However the texts that we have here, for the 8th and 10th Sundays after Trinity, prompt certain thoughts in me that having been lurking for a while. These texts do not show a very attractive face of Lutheranism. They express a combative spirit against other Christian communions that outdoes Belfast in the old days with its willingness to invoke the torments available to the Almighty Himself as the righteous punishment for their doctrinal errors. If only one thought it had anything at all to do with the Creator, if there is a Creator. Instead it parades the entirely human sentiments of resentment, alienation and vindictiveness under a banner of theology, the only relief being found in some texts that content themselves with the contemplation of what miserable sinners we are. Relating this to the music, I shall take the last cantata here, # 102, as a random example. The aria Weh der Seele is certainly pensive and sad in a way I know very well from Bach, but its spirit is not one of putting the frighteners on us, which is what the text is doing. As for the fine sturdy chorus at the start, and the arioso Verachtest du, if you did not know what the meaning of the words is, would you guess their truculence from the tone of the music? This makes me wonder about quite a lot that Gardiner has to say regarding Bach's word-setting. I do not really believe that Bach fitted words to music in anything like the micro-manner that Gardiner keeps looking for, and certainly not words such as we have here. It seems to me that Bach's Lutheran faith was one of radiant certainty, and that his inspiration was entirely musical and not really dramatic in the way Gardiner purports to find. Any `drama' in Bach is stylised and formal, because he knows who he is and stays true to himself. Ally that sublime faith to that even sublimer inspiration and what will be created is a purely musical masterpiece, the tone appropriate in a general way to the associated sentiments, but the details an entirely musical matter and not at all a literary or pictorial one. Constant and intense immersion in music as toweringly great as this music is benefits Gardiner as an interpreter, but it is almost bound to skew his judgment as a critic and commentator. Some of his comments recall to me the great Donald Francis Tovey, for whom anything Bach or Beethoven did instantly eclipsed all that the rest of musical creation had ever attempted along lines that were even remotely similar. Regarding the aria Dein Wetter in cantata 46 Gardiner enquires rhetorically `Is it just the superior quality and interest of this music that makes it so much more imposing, and indeed more frightening, than any operatic "rage" aria of the time by, say, Vivaldi or Handel?' Whoa, please. Hold on. Handel, are we to understand, who spent his life as an impresario and who was thought by no less than Beethoven to be the superior of Bach himself, could not in his entire career equal what a contemplative Kapellmeister could achieve in a single foray into the idiom? The danger with unwise and excitable opinions like this is that Handel is gradually returning to the musical mainstream from which he was exiled for so long, and I am sure that people are gradually recognising, as I am myself, what Beethoven meant. It never deterred Tovey from sweeping generalisations that he did not, in the rigour of the expression, know what he was talking about, but Gardiner I am sure does, and perhaps he will come to agree that partisanship of this kind is better reserved for sporting contexts. Top class all the same." |