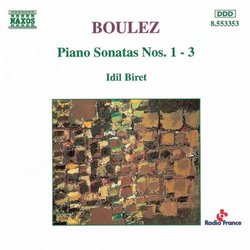

| All Artists: Pierre Boulez, Idil Biret Title: Boulez: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-3 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Release Date: 9/19/1995 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Sonatas, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 730099435321 |

Search - Pierre Boulez, Idil Biret :: Boulez: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-3

| Pierre Boulez, Idil Biret Boulez: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-3 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsWonderful recording of Boulez's Second Sonata 02/03/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "A lot of people like Pollini's recording of Boulez's Second Sonata. I think it's very good. But it was Idil Biret's recording that made me fall in love with the piece. Biret shapes the lines more vividly, and her dyanmic range is astounding. Such things really do count while playing such a piece! Pollini is rather monochrome in comparison. In fact, I dare say Biret's performance of the Second Sonata is the sort of thing one might use to convince people of the intensity and beauty of Boulez's music.I'm not entirely sure about the other Sonatas though. Biret does a good job with the first movement of the First Sonata (with a wonderful sense of disturbed stillness), but the final movement is not as fiery as I've heard in a now unavailable Erato recording (I think the pianist was Pierre-Laurent Aimard). And, to be honest with you, as a composition I don't care much for the Third Sonata. But this is a relatively cheap CD, and the priceless interpretation of the Second Sonata makes it a real bargain" First is pinnicle,less the Second,least the Third scarecrow | Chicago, Illinois United States | 08/14/2000 (4 out of 5 stars) "This is a hard call;Pollini's monochrome timbre(in the Second Sonata)intentionally creates the rhythmic (furious) untrampled drive the work needs which is exciting,you don't need a listening agenda to consume this violence.Pollini would rather have some purest conception at work(as here in his early Eighties reading) sacrificing all, than drifting aimlessly over the generous violence the Second imparts.The Second Sonata, for the most part moves at such a fever pitch that many times you are not appraising the gradations of timbres(as Biret strives for),but simply the motions and movements of registers which occur in rapid-fire quicksilver formations over the entire keyboard. That's why Biret's First Sonata reading is far superior than anyone I've heard,save Fredric Rzewski,Biret knows how to construct drama and the First still had remainders and leftovers of that for the young Boulez was trying to get,subvert tradition out of his creativity.The First Sonata still has its registral movements in fairly obvious successions,and Biret shapes those outlines admirably. Her Second(I agree) lacked demonic spirit which you find in Pollini.Boulez(at the time of the Second) was reading Antonin Artaud and the Theatre of Cruelty mixed with the surreal poetry of post-war occupied France,somewhat disturbing ambiences for a man in his Twenties.It's incredible that the young Boulez had only a clangorous upright piano to try out his revolutionary new work, this one.The Third Sonata is rather opaque and ill-focused, and I've never heard anyone yet who plays it with any degree of conviction,Aimard,Rosen.And Biret here as well strives for summoning a mystery out of this indeterminate mapping of the beautiful multi-coloured score.As a footnote: I still admire Yvonne Loriod playing the Second,she brings an enraged demeanor to the entire work short changing the mystery that may be the result in the rather surreal second and third movements.I heard Rzewski play the Second at Carnegie Hall and in Chicago in the early Seventies,and he stays fairly close to the inflammatory enragement of Loriod." Easily the best of all the different recordings Luke birkla | Leeds, UK | 04/05/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "Idel Biret's incredible rendition of the three Boulez Piano sonatas reigns untrammelled by the glossy facade of the Deutsche grammaphon and Montaigne efforts.

There is a sense of will, Biret guides the listener inexorably through the music with consumate artistry, giving the right amount of tension and repose to every corner of Boulez's music. Biret brings out the ravelian nature of the second sonata better than anyone else. wonderful" |

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1

Track Listings (11) - Disc #1