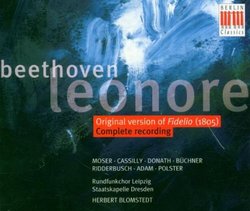

| All Artists: Siegfried Lorenz, Ludwig van Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt, Dresden Staatskapelle, Leipzig Radio Chorus, Leipzig Radio Symphony Chorus, Edda Moser, Helen Donath, Eberhard Büchner, Reiner Goldberg, Ricardo Cassinelli Title: Beethoven: Leonore (Original Version of Fidelio) Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Berlin Classics Release Date: 3/19/1996 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 782124114022 |

Search - Siegfried Lorenz, Ludwig van Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt :: Beethoven: Leonore (Original Version of Fidelio)

| Siegfried Lorenz, Ludwig van Beethoven, Herbert Blomstedt Beethoven: Leonore (Original Version of Fidelio) Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsFrom American Record Guide Record Collector | Mons, Belgium | 12/21/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) ""In 1814, as Beethoven worked to revise Fidelio for the second and final time, he wrote that he 'could have composed something new far more quickly than patch up the old with something new, as I am now doing.' On balance we would probably be musically richer today had he given us a brand new opera and left Fidelio alone. The work performed here--the opera in its original, 1805 version--would doubtless have found a secure place in the repertory in any case. But there is no doubt that the later version is a stronger, tighter work. And learning how it got that way makes for no end of fascination.

"A full account of the changes could fill an entire issue of this magazine. Mostly it was a matter of condensing. Two entire numbers--both from the early, 'domestic' part of the opera--are omitted completely; they are good to hear--especially the duet for Leonore and Marzelline with its concertante solo strings--but they add little to the drama. The finales are significantly improved. Instead of the telling, intricate ensemble Beethoven devised to end the first act in 1814, the original version has a rather blustery piece for Pizarro and chorus. And the conclusion of the opera--even though Beethoven worked with the same musical ideas--is both more moving and more exciting in the final version. But the duet 'O namenlose Freude,' in the original, much fuller version (prefaced by an expressive accompanied recitative) makes a strong impact, for is not yet clear that the danger is over for Florestan and Leonore as they sing of their joy at being reunited. "There are also many cuts of just a few measures in most of the numbers that were otherwise not heavily revised. These go beyond the kind of mindless cuts of four or eight measures that have become traditional in other operas, for they often change the shape of the music in an incisive way, so that the earlier forms do indeed often seem needlessly protracted. The early version, for instance, has Pizarro utter (wholly superfluously, in retrospect) the word 'Ah!' between the first and second lines of his aria. On the other hand, there are some choice little passages that one wishes had been spared the knife. Incidentally, the practice of referring to the original version (as well as the 1806 revision) as 'Leonore' is now common, but the opera was called 'Fidelio' from the beginning at the theater's insistence to distinguish it from other operas based on Jean Nicolas Bouilly's French libretto; Beethoven himself preferred the title 'Leonore.' "Exploring the original version through the means of this accomplished performance proves to be much more than a scholarly exercise. Edda Moser is a bright-voiced, feminine Leonore. A couple of the climactic moments--'Wer du auch seist' in the grave-digging duet, for instance--are a little mild, but in general she sings with much fervor; and she has the technique for the long coloratura passages Beethoven later removed from her aria. Richard Cassily is an expressive, forthright Florestan. His opening cry of 'Gott! welch Dunkel hier!' is paler than Jon Vickers's, but that is partly because the music itself is paler. The rest of the cast would enhance any Fidelio performance--Theo Adam's lean, menacing Pizarro, Karl Ridderbusch's smooth, amiable Rocco, and the lovely Marzelline of Helen Donath, which makes hearing her role in its larger form an added pleasure. "At the outset, Herbert Blomstedt and the Staatskapelle Dresden give an exciting account of the Leonore Overture No. 2, which is how the 1805 version begins. It sets the tone for the well-organized, energetic performance that follows." " |