| All Artists: Johann Sebastian Bach, John Eliot Gardiner, English Baroque Soloists, Gillian Keith, Katharine Fuge, Christoph Genz Title: Bach Cantatas, Vol. 6: Köthen/Frankfurt Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: SDG - Soli Deo Gloria Original Release Date: 1/1/2007 Re-Release Date: 10/9/2007 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Historical Periods, Baroque (c.1600-1750) Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPCs: 843183013425, 829410219389 |

Search - Johann Sebastian Bach, John Eliot Gardiner, English Baroque Soloists :: Bach Cantatas, Vol. 6: Köthen/Frankfurt

| Johann Sebastian Bach, John Eliot Gardiner, English Baroque Soloists Bach Cantatas, Vol. 6: Köthen/Frankfurt Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

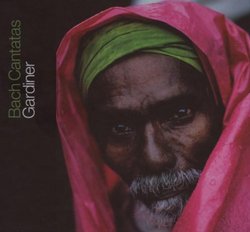

CD ReviewsBravo! BWV 77 Discussed further... Vegan Daddy | Roslyn, WA | 11/04/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "Again, Gardiner and the Monteverdi Choir/English Baroque Soloists deliver. This particular set is recorded on location in Köthen and Frankfurt corresponding to the cantatas composed for the twelfth and thirteenth Sunday Trinity respectively. Vol. 6 Köthen/Frankfurt (2 CDs) contains the following cantatas (for those of you looking at this page for reference by BWV number as well): Cantatas for the Twelfth Sunday Trinity BWV 69a - Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele BWV 137 - Lobe den Herren, den mächtigen König der Ehren BWV 35 - Geist und Seele wird verwirret Cantata for the Thirteenth Sunday Trinity BWV 77 - Du sollt Gott, deinen Herren, lieben BWV 164 - Ihr, die ihr euch von Christo nennet BWV 33 - Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 77, recorded here, was the main reason for my purchase of this volume. Scored for Tromba [Chorus, Aria, and Chorale movements], Oboe I/II, Violino I/II, Viola, SATB, Continuo, this cantata is one of beauty (aurally) and heart (textually). To experience the beauty one must only listen but the text and the music are richer in more than heart. Du Sollt Gott, deinen Herren, Lieben opens the cantata in full chorus with trumpet. Bach is sneaky to use a Luther hymn as the trumpet/continuo part. This introduces the theme to this cantata - what does God require of us? - To love the Lord God with all thy heart and with all thy soul... The fifth movement is a standout for the trumpet, performed here using the tromba da tirarsi (slide trumpet). Bach infuses the text to what is producing it aurally - the trumpet. Historically, the trumpet signifies triumph and glory or pomp and power. It is played in the keys of C, D and Bb (Eb and F more in the rococo). Bach uses it in the quite unfamiliar key of d minor which equals plenty of c sharps [quite a nasty note on the historical trumpet of their time] to highlight the text of this movement - Imperfection. 17 times the C# appears under the text [translated]: Oh there remains in my love A lot of imperfection. I often have the will To do what God says But I lack the possibility. Friedemann Immer argues that "Bach used the trumpeter's failing abilities to produce perfect C-sharps [on the historical trumpet] to symbolize man's failing ability to fulfill to God's 10 commandments. The text in the aria expresses the human "incapacity" or "inability" to practice divine love. Had Bach ordered the use of a slide trumpet [tromba da tirarsi], it would have been easier to play perfect C-sharps. But then the incapacity to love the Lord, could not have been symbolized by the trumpeter failing to play the C-sharps."* Fortunately to the modern listener, Gardiner chooses to ignore this theory and instead delivers us a beautiful sound. *-Text from International Trumpet Guild website." Wonderful Music Making Kenneth J. Luurs | Oak Park, IL USA | 11/05/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "I have a lot of Bach cantata recordings in my collection - the complete Koopman, Harnoncourt and Rilling - along with a scattering of others - including all of the Richter. Having said that, I think this series is about as wonderful a recording project as I have encountered. I love every aspect of this series. The recordings are sonically stunning. The performances are first rate. It is almost like discovering a new continent of stunningly beautiful music. Sadly, because there are so many cantatas, many people don't bother to explore this new world. I recommend that you do. Actually, you can pretty choose any of the volumes released to date to start listening. Heck, I love the covers of these CD's - some of the most visually stunning ever employed in the classical field. If you already have 4 versions of the Beethoven symphonies and need something new...I can't think of a better place than to buy a volume of these every month - and treasure the experience. " Why do I bother? Teemacs | Switzerland | 11/04/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "The French expression is "rien à dire" (nothing to say, with the connotation that all superlatives are exhausted). This is one great series. The highlight of this one is BWV137, "Lobe den Herren, den mächtigen König der Ehren", which churchgoers would recognise as the hymn "Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation". My one quibble is that Gardiner takes the magnificent opening choral fantasia, with its trumpets and drums, a shade faster than I would like, which takes away some of the magnificence of one of the greatest hymn tunes ever written. However, the Monteverdis handle it with aplomb.

The other cantatas are less well known (to me anyway), and they receive great performances. Recommended for all Bach lovers." |

Track Listings (18) - Disc #1

Track Listings (18) - Disc #1