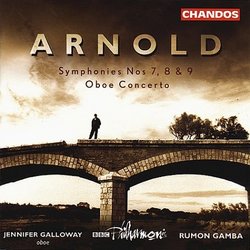

| All Artists: Malcolm Arnold, Rumon Gamba, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Title: Arnold: Symphonies nos 7, 8, & 9; Oboe Concerto Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Chandos Release Date: 9/25/2001 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Instruments, Reeds & Winds, Symphonies Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 095115996720 |

Search - Malcolm Arnold, Rumon Gamba, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra :: Arnold: Symphonies nos 7, 8, & 9; Oboe Concerto

| Malcolm Arnold, Rumon Gamba, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra Arnold: Symphonies nos 7, 8, & 9; Oboe Concerto Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsStupendously accomplished final symphonic tryptich Philippe Vandenbroeck | HEVERLEE, BELGIUM | 10/10/2009 (5 out of 5 stars) "Ramon Gamba, who took over the baton from Richard Hickox in this Chandos cycle of Arnold symphonies, completes this recording project with a quite stunning final tryptich.

The Seventh, one of the darkest in the cycle, is presented as a no holds barred, recklessly uproarious affair. Mervyn Cooke comments in the liner notes on the interpretative leeway that has characterised this work, mentioning that "... in Arnold's broadcast the symphony lasted little short of one hour, while the official catalogue of the composer's work gives the duration as forty-five minutes and the full score specifies thirty-eight minutes!". In this recording, the BBC Philharmonic stunningly delivers the work in ... under thirty-two minutes! Particularly the first movement, allegro energico, is played at a breathtaking tempo. To reinforce the point: Gamba comes in at just over 13 minutes whilst Andrew Penny on Naxos, an obvious comparison, takes more than three minutes longer. So it's rather "furioso" than "energico" but there is no denying that Gamba's vision works. It's not only a matter of tempo. There's bite, grit, hard-hitting anger and grief in this reading. It's another step in the fearsome exploration of progressive dissocation that Arnold had engaged in in his Fifth and Sixth symphony and which, incidentally, is mirrored in his personal life which would lead to a complete breakdown in the late 1970s. Perplexingly, he chose this spectral, nightmarish work as a musical portrait of his children (Katherine, Robert and Edward associated with first, middle and last movement respectively). Katherine later commented: "I can see my brothers in the last two movements but as regards the one about me - it's very energetic and even violent - I think I can see my father in that." The second movement starts as a mournful meditation with a trombone solo in a key role. Bleak percussion motion on the tom-tom leads to a frenzied crescendo, punctured by three ominous strokes on cowbells, culminating in a fortissimo statement of the movement's main theme before it dies out in a quiet coda. The brief finale returns to the savage atmosphere of opening movement. Unexpectedly, an Irish folk band strikes up creating a surreal mood. The symphony concludes abruptly with another three strokes on the cowbells, followed by a sequence of five curt, ambiguous chords. In between the destructive whirlpool of the Seventh and the dark monolith of the Ninth, the Eight symphony - a three-movement work of just under 25 minutes - appears somewhat as a less demanding intermezzo. The insouciance is deceptive, however, as Arnold started to work on it only a month after a severe psychotic episode and while still an in-patient in a psychiatric ward. The first movement strikes up in a veritable panic but soon gives way to a conspicuous, jaunty "Irish" march punctured by violent outburst. An argument ensues which in its angular Beethovenian drive, its tectonic complexity and coolheadedness reminds me somewhat of that other British symphonist, Robert Simpson. The slow movement is a restrained Andantino, built around a elegiac, chorale-like theme. Gamba and his BBC forces play this beautifully. The music breathes, seems weightless at times. In the sprightly finale, however, Gamba for once seems to misjudge the tempo. A full minute faster than Penny, the proceedings seem a tad breathless. The Ninth Symphony comes after a long period of creative sterility. It is the highlight of Arnold's last part of his life during which he was more or less kept afloat by his caretaker Anthony Day (and the score is dedicated to him). Initially it was not well received and it took 5 years of untiring advocacy of close friends to get it heard for the first time. Faber, Arnold's long-time publisher, could never even be persuaded to publish the work (Novello took it upon themselves instead). Friends and critics who inspected the score were startled by the sparsity of the orchestral writing with page after page of empty staves. They thought the work was "unfinished", the work of a composer who had largely lost his creative powers. Those who meant well with him advised against publication as it would damage his reputation. But the conductor Sir Charles Groves, one of those unwavering believers, was adamant that the work needed to played and heard in order to assess its true merit. And he was right. Despite the bracing tempo indications, the music has an autumnal feel from the very first bars. There is warmth and tenderness, but it's enveloped in an uncomfortable, bone-hard chillness. The allegretto is formally a most simple, loosely woven set of repetitions of a hauntingly beautiful tune that is gently tossed around the orchestra, alternatingly taken up by the strings and by the winds and brass, either solo or in pairs. The third movement is one of those classic, rambunctious Arnold scherzi (here with perky, Prokofievian overtones), ending abruptly, questioningly. In no way it prepares us for the long, sad farewell that concludes the work (and with it the whole of Arnold's symphonic oeuvre). It's a sparse, meandering, gloomy meditation, predominantly given to the strings, pianissimo (almost throughout), on basically a single theme. It's even more controversially "simple" as the slow movement of his Fifth symphony. Most commentators compare this movement to its pendant in Mahler's Ninth, but I feel a comparison with Beethoven's Arietta - Adagio molto semplice and cantabile - from his last piano sonate, opus 111, is more apt as both movements are based on a daringly austere set of variations (or repetitions or, even better, improvisations) of what is basically an artless theme. The final chord in the Beethoven sonata is a simple C major. Arnold's symphony ends with a tender, tentative modulation into D, a long chord which Arnold thought should been held "low and dying, so that at the end there should be no applause and then you know you've just won through." As Charles Rosen writes about op. 111: "The modesty of the final chord is significant." The music's impact is heightened by the BBC Philharmonic's stupendous dash and dedication and by a very brilliant, but also meaty 24-bit recording from the Chandos team. I think this set is a must-have for Arnold admirers. However, in addition to this recording I would certainly recommend the Naxos recording of the Ninth as a complement. It is expertly delivered by Andrew Penny and the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland but there is an additional great attraction in the form of a short, truly captivating conversation between Penny and the late Arnold about his last symphony. The terseness of the composer's replies is quite revealing of his state of mind in the last years of his life. I almost forgot to mention that the set of three symphonies is complemented by an enjoyable recording of the first Oboe Concerto, a much earlier work. It would, perhaps, have been more instructive to include one of Arnold's contemporaneous works such as the Philharmonic Concerto, op. 120 or the Concerto for Recorder, op. 133." |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1