Wonderful! Bravo!

K. Farrington | Missegre, France | 01/19/2001

(5 out of 5 stars)

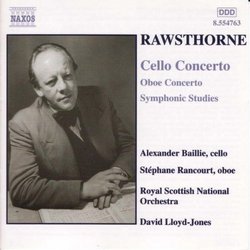

"It seems inconceivable that for just under six bucks you can get a CD of this quality, played so brilliantly, with the added bonus that the music itself is new. Well, the music is not exactly new but to my ear every bar sounds as fresh and as new as when this young composer started penning his works in the 1930's. Also I have not heard the Symphonic Studies for some years now; I believe that I heard them on vinyl over 20 years ago. The music has a muscular quality compared to most English Music at the time, it is a concerto for orchestra that uses all the components to their virtuosic best. The players seem to relish playing this unfamiliar stuff that keeps the listener enthralled throughout. The Cello Concerto is a unjustly neglected piece, to my mind better than the Delius and Bax offerings in the same genre. The younger composer Rawsthorne seems to be able to go that extra mile in giving us surprises and his premature death is one more loss to our musical heritage to go down with Gerald Finzi whose gentler style somehow compliments Rawsthorne in that together they show respectively the kind and the gritty characteristics of the English psyche. We are norw getting more CDs with Naxos doing their Rawsthorne cycle and Chandos with their recent release of Film Music providing us at last with a wealth of great sound from this underrated and self effacing genius. Top Marks!"

The Raw Power of Rawsthorne

Thomas F. Bertonneau | Oswego, NY United States | 02/05/2001

(5 out of 5 stars)

"Where does Neoclassicism begin? Possibly in Tchaikovsky, who wrote a "Rococco Variations" for Cello and Orchestra and a Suite called "Mozartiana." Italian composers such as Alfredo Casella and Gian-Francesco Mailpiero looked back to Monteverdi, Gabrieli, Vivaldi, Tartini, and Scarlatti in composing their large bodies of work for orchestra. Stravinsky went on a "Back to Bach" binge and Hindemith wrote a set of chamber concertos that answered Bach's Brandenburg set from the viewpoint of the twentieth century. Feruccio Busoni lies somewhere in the mix, with works like the "Fantasia Contrapuntistica." But the phenemonen is wider than any of these comments suggests. Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971), a British composer, deserves mention under the rubric. He employed devices that we associate with the Baroque: Canon, Fugue, Passacaglia (which he, like Henry Purcell, called Chaconne), and the Fantasy, or Variations. The middle movement of the lively Concerto No. 1 for Piano (1939 - revised 1942) takes the form of a Chaconne, and both outer movements exhibit the moto perpetuo character of Baroque music. The three symphonies (1950, 1959, 1964), like the First Piano Concerto, use imitative forms associated with the Eighteenth, rather than developmental forms associated with the Nineteenth, Century. The prototype of all these works is the remarkable "Symphonic Studies" (1938) for orchestra, premièred at the Warsaw ISCM Festival in 1939. The "Studies" constitute a symphony in all but name, casting the variations-on-a-theme in the form of five large panels that correspond to the movements of a more explicitly sectional work. Thirty years ago, this work appeared on a Lyrita LP. Its dark colors and rather thick chromatic writing fascinated me. Three decades make the chromaticism seem less harsh than it did at the time, but the "Studies" retain their power as a work of extraordinary polyphonic concentration. The final segment is a fugue. It is as convincing a fugue as any composer of the Twentieth Century contrived to write. Truly, Rawthorne's "Symphonic Studies" can rival Schoenberg's "Variations for Orchestra" as a virtuoso display of thematic transformation colored forth in orchestral garb. The "Studies" also takes its place in a flock of British compositions that employ extremely rigorous variation-technique: Sir Edward Elgar's "Enigma Variations," Ralph Vaughan Williams's "Tallis Fantasia," Sir Arthur Bliss's "Discourse for Orchestra," and William Walton's "Variations on a Theme by Hindemith." The Cello Concerto (1966) comes from late in Rawsthorne's life. It returns to the darkness and concentration of the "Symphonic Studies" and is one of his thorniest works. For diversion, we also get the charming Oboe Concerto, with strings. Naxos has given us the two Violin Concertos, a disc of chamber works, a disc of string-orchestra works, and now this first-rate coupling of the "Studies" and the Cello Concerto. I do hope that they provide us with the three symphonies, with the three piano concertos (one of them, the last, for two pianos), and with the three cantatas - "Medieval Diptych," "Carmen Vitale," and "The God in the Cave." At the asking price, it would be a shame to pass this up."

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1