One of the most surprisingly satisfying budget recordings.

M. Stoltenberg | Phoenix, AZ USA | 03/24/1999

(4 out of 5 stars)

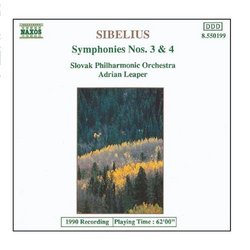

"Of the set of Sibelius symphonies conducted by Adrian Leaper for Naxos, the 3rd & 4th are by far the only worth listening to. The sound quality is shockingly good. This is made apparent by listening to the opening movement of the 4th Symphony. I compared the tempos in this recording to the one on BIS conducted by Neeme Jarvi and I was taken aback by how Leaper takes his time and allows the haunting and disturbingly beautiful sonics of the Scandinavian Arctic regions to creep over us on an even more expansive level than Jarvi's. The opening to the 3rd is exciting as the strings take us on a worshipful journey comparable to Beethoven's introduction to his Pastoral Symphony. I have read many unfairly derisive reviews of Naxos recordings in regards to recording quality. These statements hold true for the other Sibelius symphonies on Naxos (#1, 2, 5, and 6). However, #3 and #4 on this recording are a glorious exception."

Magic Sibelius

Gary D. Warner | Saginaw, MI | 08/06/2008

(5 out of 5 stars)

"A splendid performance AND recording of the great Sibelius' undeservedly less appreciated symphonies; a fine value buy to boot. The magically charming effect of my favorite composer's consistently fresh, uniquely innovative originality, truly defies description. His music must be experienced. Like all great artists, Sibelius has a readily identifiable style, yet each symphony has its own distinct character. Having now personally discovered these works in particular, I feel a need to take exception with music critic, Ted Libbey's laconic remarks about Symphony No. 4. While bypassing it for recommendation in the first edition of his book, "The NPR Guide to Building a Classical CD Collection," he stated, "...the grimly pessimistic Fourth embraces a dissonant language that brings it to the very edge of harmonic dysfunction." (P. 167). To my mind Mr. Libbey's description made this work sound like something morose, cacophonous (at least nearly so) and annoying--to be avoided--and that is exactly what I did for a long time. But the more I thought about it, the assessment did not ring consistent with my knowledge of Sibelius' artistic integrity. Frankly I can think of several other composers' works to which it would be far more appropriately applicable. The author's assertion remained unchanged in the second edition, however, as an apparent afterthought, it did make it into a short list of favorites in the back. (In either case, it should be noted that Libbey was not referencing this recording. My responses are limited to what he had to say about the composition only).

To be fair, I have personally benefited greatly from Libbey's invaluably informative analyses, but in this instance I believe his appraisal is too breviloquent to be enlightening and thus tends to come off as superficial. At the same time, I'm potentially willing to concede that my impression of his meaning may not be entirely sagacious. Sibelius indeed described the Fourth as psychological. As such I'll heartily agree to its having an introspective aspect, and yes, the entire third movement, Largo, I'll grant is darkly brooding. But by no means would I characterize the entire symphony as "grimly pessimistic". Could a case be made for such a conclusion? Of course! Unfortunately, Mr. Libbey didn't develop one. Moreover, in the final analysis, I believe, at least as far as personal perception is concerned, this sort of verdict can only be subjective. Mine, is that there are very few moments I would call overtly dissonant, and they are quite fleeting amidst this symphony's overall fascinating and invigorating loveliness. While describing it as austere, Sibelius biographer, David Burnett-James wrote, "The Fourth ... is by no means all gloom and desolation. There is a story that one day Sibelius was out walking with a friend when they came upon a sudden glow of sunlight on a valley. Sibelius stopped and, pointing to it, said: 'I have put that into my Fourth Symphony.'"

Updated thoughts: 10-25-09

Even though I knew it well, honestly now taking a step back, I have since rediscovered that dissonance, as a relative concept, can certainly be less than obvious--even stealth--especially to untrained ears.

In point of fact, dissonance is necessary. For music to be good and interesting, it must have an element of tension (in varying degrees) which alternates between dissonance (or say conflict--if only philosophically as opposed to tonally) and consonance. Then in the actually tonal, i.e. clashing sense, dissonance (again in relative degrees) ranges from subtle or concealed to overt or gratuitous, if you will. Music then is analogous to life, naturally--not all harmonious, nor should it be--otherwise no concepts such as resolution of conflict or triumph over adversity would exist; our personalities likewise would have neither depth nor strength of character. Thus if music does not at least abstractly evoke or reflect these and similar ideas, its value is vapid, with little if any hope of rising above the level of inane tedium.

Author Alex Ross, in writing about the tonal character of Sibelius' final orchestral work, Tapiola, states, "this is dissonance of a deeper order, the kind that alters your consciousness without assaulting your ears."* This describes an essential aspect of Sibelius' ineffable genius, which critics and the public alike failed to comprehend for so long. So in further deference to the technically learned Mr. Libbey, I must humbly admit that when specifically speaking of the Fourth embracing a language of dissonance, he knows (much better than I) exactly what he's talking about. And I realize now that he wasn't actually bad-mouthing this symphony at all. Although yet paltry, I have gained a modicum of insight into the complexities of Sibelius' music, in particular, the simple fact that much of the dissonant language he employs is indeed subtle if not covert.

_________________________________________________

*"The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century;" Chapter 5, p. 169."

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1